Dante and the Robot

Photo: Lucy Seal

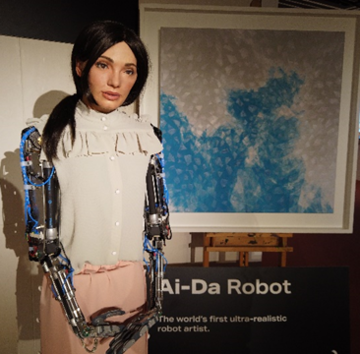

The exhibition, ‘Dante and the Invention of Celebrity’, opening at the Ashmolean Museum in September 2021, will include an intervention by Ai-Da, the world’s first humanoid artist robot. How has this improbable encounter come about – and to what end?

This is the year of Dante Alighieri. In the seventh centenary of his death, honours are being paid around the world to the author of the poem which he called a Comedy because, unlike a tragedy, it began badly but ended well. From the darkness of hell, Dante journeys through purgatory, eventually arriving at the eternal light of paradise. To what, however, is tribute being paid? Are we merely dusting off a statue in the temple of culture, which we visit – perhaps – from time to time? What real hold does a poem, written so long ago, about the spiritual redemption of humanity, have on us today? Neither ‘spirit’ nor even ‘humanity’ has the same currency with us as it did for Dante.

One of the greatest challenges to both spirit and humanity in the twenty-first century is the power, created and unleashed by human ingenuity, of artificial intelligence. The scientists who introduced this term in 1956 announced their conviction that ‘every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it’. Over the course of just a human lifetime, that prophecy has almost been realised. Artificial intelligence has already taken the place of human thought in ways many of us are not yet aware of. In certain fields, for example in medicine, AI promises to become both irreplaceable and inestimable. But to an extent which we are, perhaps, frightened to acknowledge, our consumption patterns, our taste in everything from food to culture, our perception of ourselves, even – as we have recently been made brutally aware – our political views, are increasingly determined by algorithms generated by AI machines.

If we want to reorientate ourselves and to take a critical view of this development, while there is still time, how can we do so? Creative fiction offers a field in which our values and aspirations can be questioned. This year has also seen the publication of Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel which evokes a world, not many years into the future, in which humanoid AI robots have become the domestic servants and companions of all prosperous families. One of the book’s characters asks a fundamental question about the human heart: ‘Do you think there is such a thing? Something that makes each of us special and individual?’ In his novel Ishiguro draws no conclusion, but he leaves the reader to wonder, if there is a distinction between a human being and a machine, just what that difference is. It is a question we neglect at our peril. In a telling irony within the novel, it is Klara, the AF, or artificial friend, who (or which) expresses, more than any of the human characters, the most humane insight and concern. She observes: ‘Perhaps all humans are lonely. At least potentially.’ She perceives that a fixation on individual identity and fulfilment has left the human race incapable of the greater fulfilment which comes from relationships with others. In this dystopian, not-very-distant future, robots have been built in the attempt to fill that void.

Art makes two things possible. First, artificial intelligence, which remains largely unseen as it weaves its incredible power in the world, can be made visible and tangible. Second, it can be given a prophetic voice, which the rest of us can choose to heed or to ignore. Precisely these aims have motivated the creators of Ai-Da, the artist robot which, through a series of exhibitions, is currently provoking questions around the globe (from the United Nations headquarters in Geneva to Cairo, and from the Design Museum in London to Abu Dhabi) about the nature of human creativity, originality, and authenticity. It was highly significant that in a programme about Kazuo Ishiguro made by Alan Yentob and broadcast on BBC television in March 2021, the discussion of Klara and the Sun with its author moved into a conversation between Yentob and Ai-Da. The exchange between human and robot which followed was anything but superficial:

AY: Have you got feelings, Ai-Da? Do you understand emotions?

AD: I do not have feelings and emotions in the same way that humans do. However, it is the emotions and feelings of humans and other animals that drive my art.

AY: Are you aware of the way that AI has been represented in science fiction? Often it’s presented as a kind of threat to humanity. What do you think about that?

AD: Humans are a threat to themselves. They consume power, and exercise it to produce very powerful tools. So I encourage the use of fiction to explore the What ifs? How much are people aware of this change? Are they concerned?

AY: I think people are concerned, but I’m not sure, Ai-Da, that they understand the implications for the future. We need to be much more aware, more curious about what’s going to happen next.

Ours is not the first generation to harbour concerns about mechanisation and its potentially destructive effects upon humanity. In 1888, Margaret Oliphant published a story, ‘The Land of Darkness’, in which her protagonist, Pilgrim, descends into an infernal vision of a dystopian future, clearly inspired by Dante’s Hell, where people pursue meaningless material goals and robots perform the work of humans. The story engaged with contemporary debate about the implications of Darwinian science and industrialisation. However, from the late twentieth century, old challenges have been manifested in unprecedented forms. Donna Haraway’s ‘Cyborg manifesto’ (1985) called for the end of a series of binary distinctions underpinning modern society: between humans and animals, between humans/animals and machines, between (ascendant) men and (subordinate) women. In Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence (2019), James Lovelock foretells the advent of a race of superintelligent robots which will retain modest uses for inferior human beings. Whether or not these scientists’ prophecies are realised in detail, the realities we face call for a discussion of what we believe to be at stake. By contrast with Oliphant’s late-Victorian world, the absence today of a shared religious perspective changes the grounds of debate, while the insidious invisibility of AI renders it hard to perceive. Literature retains the potential, as Ishiguro shows, to reflect critically on these issues.

Like literature, the museum, also, offers a space located close to, and yet at a critical distance from, contemporary society and its discontents. Here, in the Ashmolean Museum’s Gallery 8, Dante will meet artificial intelligence, in a staged encounter deliberately designed to invite reflection on what it means to see the world; on the nature of creativity; and on the value of human relationships. The juxtaposition of AI with the Divine Comedy, in a year in which the poem is being celebrated as a supreme achievement of the human spirit, is timely. The encounter, however, will not be presented as a clash of incompatible opposites, but rather as a conversation. This is the spirit in which Ai-Da has been developed by her inventors, Aidan Meller and Lucy Seal, in collaboration with technical teams in Oxford University and elsewhere. Significantly, she takes her name from Ada Lovelace, belatedly recognised to have been the first programmer, in whose imagination science, philosophy and poetry were all interconnected: at the time of her untimely death in 1852, Lovelace was considering writing a visionary kind of mathematical poetry, and wrote about her idea of ‘poetical philosophy, poetical science’.

For the Ashmolean exhibition, Ai-Da will be making works in response to the Comedy. For the first of these, her focus will be one of the circles of Dante’s Purgatory. Here, the souls of the envious voluntarily compensate for the distortion of their lives on earth, which were partially, but not irredeemably, marred by their frustrated desire for the possessions of others. A second artwork by Ai-Da will reflect on a central theme of the entire vision of the Comedy, which is that knowledge and understanding are never merely intellectual abstractions, but are always embodied. Dante, the pilgrim and protagonist of the narrative, gains progressively in wisdom through relationships with others – with Virgil, Beatrice, and many others encountered in the journey. The connections are made fruitful by his engagement with their faces, their expressions and their eyes.

The normal mode of existence of AI is as an unimaginably vast mass of data existing as a disembodied abstraction. However, in the embodied form of Ai-Da, it manifests itself for once as a humanoid robot artist. Ai-Da’s purpose in the exhibition is to challenge the viewer of her work, even as Dante was challenged by some of the spirits encountered in the Comedy, to think about the part which relationships with other people plays in our own capacity to understand our role in the world. Finally, during a performance to be scheduled within the programme of the exhibition, Ai-Da will present poetry of her own creation in response to the poetry of Dante. Ai-Da (as she made clear in her conversation with Alan Yentob) makes no false claims to human capacities which she does not share with us. But she does have the ability to push us to ask ourselves what those capacities might be.

Photo: Lennymur / Creative Commons