Dante at the Ashmolean: Three Curator’s Highlights

Dante at the Ashmolean: Three Curator’s Highlights

Dante: The Invention of Celebrity is now open to the public at the Ashmolean Museum. Built around the Divine Comedy, which describes the poet’s vision of Hell, Purgatory and Paradise, the exhibition explores in particular the theme of fame: a subject no less interesting to ourselves than it was to Dante.

Curating this celebration of Dante, in the 700th anniversary of his death, has been a rare pleasure, both for the collaboration with the Ashmolean’s outstanding exhibitions team and for the opportunity to search Oxford’s collections for unfamiliar objects and images relating to the poet. Oxford is a good hunting-ground, for a particular reason. During the Romantic nineteenth century, when enthusiasm for Dante spread rapidly across Europe and beyond, English readers of the Comedy were amongst the most dedicated. Oxford became a leading centre for the study of the poet. The Oxford Dante Society was founded in 1876: the second such association to be formed, after the German equivalent in 1865; the Dante Society of America followed in 1881. The chief founder of the Oxford Dante Society was Edward Moore, the Principal of St Edmund Hall, whose vast work on the surviving manuscripts of the poem led to the publication of the ‘Oxford Dante’ in 1894, subsequently reprinted in revised editions. For some time this was universally regarded as the authoritative text of Dante’s works. Paget Toynbee, another leading member of this Oxford circle, produced the standard edition of Dante’s letters in 1920.

‘Death-mask’ of Dante.

Plaster, 19th-century. Bodleian Libraries.

One of my favourite works in the Ashmolean display was presented to the Oxford Dante Society in 1879 by a highly eccentric English lover of the poet, for long resident in Florence. This was Seymour Kirkup, whose strange house on the Arno bridge was the scene of mystical encounters, allegedly with the spirit of Dante himself. Having obtained what he believed to be the ‘death-mask’ of the poet, Kirkup sent a copy to Oxford. His gift was minuted by the Society:

Baron Kirkup having at the suggestion of Signor de Tivoli [Lecturer in Italian at Oxford and a member of the Society] kindly presented to the Society a Cast from the Mask of Dante in his possession, which formerly belonged to Signor Bartolini, and which has been on good grounds believed to have been taken from the Mask originally placed upon Dante’s Tomb at Ravenna. Resolved that the best thanks of the Society be conveyed to Baron Kirkup [via] Signor de Tivoli.

Bartolini, mentioned here as the maker of the original image, was a famous Florentine maker of plaster casts. Kirkup had most probably commissioned from Bartolini (in return, it appears, for the gift of a King Charles spaniel) the copy of the sculpture of Dante on his tomb at Ravenna. This portrait at Ravenna, which was believed to be based on a death-mask, is now lost. In truth, there was no death-mask of Dante; but the Romantic imagination longed to know the poet by sight, and despite its poor claim to authenticity this image became widely accepted as canonical. Indeed, as a supposed cast of the poet’s face, it was a kind of sacred relic. Kirkup’s ‘original’ found its way eventually to the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, where it is venerated as a national treasure. The Oxford Dante Society eventually, in 1920, decided to entrust its version for safekeeping to the Bodleian Library, where in recent times it has lain relatively neglected. The Library has generously permitted its display on the occasion of the exhibition, within a section devoted to changing ideas about the physical appearance of the man still known in Italy as ‘the supreme poet’.

Pierino da Vinci (after), Ugolino and his Sons in the Tower of Hunger.

Wax, ?18th-century (or ?16th-century). Ashmolean Museum.

Another work in the exhibition which has been especially exciting to discover and bring to public attention is this wax relief of a subject taken from Dante’s Inferno and made to a design by the brilliant young sculptor Pierino da Vinci – the nephew of Leonardo, and a close follower of Michelangelo. Made on commission in the 1540s for a leading Dante scholar and governor of Pisa, Luca Martini, Pierino’s relief was the first independent artwork to depict a particular scene from the Comedy. It shows a tragic story, narrated to Dante by the spirit of Ugolino in the lowest pit of Hell, of mutual betrayal: in Dante’s eyes, the worst of all sins. Ugolino, a faction leader who became ruler of Pisa, following an accusation of treachery was imprisoned together with his sons and grandsons by his bitter enemy, the archbishop of the city. In his vision, Dante finds both men frozen in ice, doomed to a perpetual embrace. Pausing from his grim work of gnawing at the neck of the archbishop, Ugolino relates the tale of his incarceration and how first his sons, then he himself, were starved to death. Giorgio Vasari, the contemporary art critic, wrote that Pierino’s work was greatly admired, and that it was acknowledged to demonstrate the power of visual art to convey the emotional force of great poetry.

The wax image was given to Oxford University in 1841; its known provenance goes back to eighteenth-century England. It now normally resides in the cold storage room beneath the Ashmolean Museum. To see it in the light, as we can in the exhibition, is to be impressed by the high quality not only of the overall design but of the detailed execution. The object remains somewhat mysterious, and its history is complicated by the existence of a number of other versions in diverse collections. A bronze, generally believed to be Pierino’s original, formerly at Chatsworth House, is now in Vienna. One of the others, in terracotta, is – remarkably – also in the Ashmolean: this was acquired in the 1860s in Florence, where it had been in a house owned by descendants of Ugolino. The Ashmolean’s wax has been assumed to be derived from a cast taken from the bronze, although in fact there are problems with this supposition. Pierino, though he surely made a bronze version of his work, evidently presented also a carefully worked edition in wax, since it is this which Vasari described in such complimentary terms. Around 1700 a version of the work was brought by a painter to England: this is not explicitly said to have been in wax, and the presumption has been that the bronze version, later owned by the Dukes of Devonshire, was the one in question. While the wax is on public view, it will be interesting to review the possible histories of a work which, in any event, is a visual highlight of the exhibition.

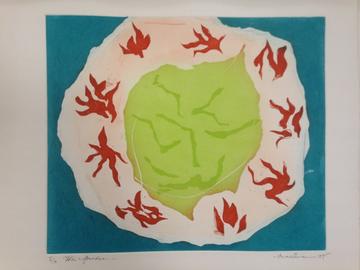

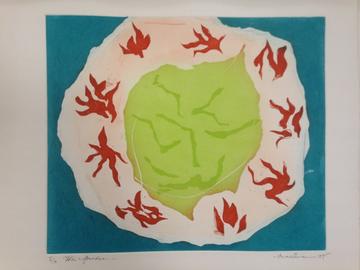

Geoff MacEwan, The Earthly Paradise.

Etching on copperplate, 2010. Ashmolean Museum.

The text of Dante’s Comedy began to be illustrated soon after its completion. Artistic responses to the extraordinary work have been enormously varied. The majority have in some way been illustrations of the narrative. Much more unusual are a small group of modern artists who, instead of providing a visual depiction of the story, have responded to the larger themes or to the mood of the poetry. The three series of Geoff MacEwan’s Dante prints fall into this latter category. They are not, however, completely abstract or without allusion to the journey within Dante’s vision. At the summit of the mountain of Purgatory lies the Earthly Paradise, where Adam and Eve lived before the Fall and their banishment. To reach this, the penitent soul must pass through a wall of burning fire. Dante at first balks at this, until Virgil, his guide, points out to him that on the other side is Beatrice – Dante’s youthful love, separated from him by her early death and now a spirit of Paradise. She waits to lead Dante up to Heaven. MacEwan radically alters the perspective to give a celestial vision upon the mountain from above, so that the Garden of Eden, indicated here by the leaf-like green form, is seen to be ringed by the purgatorial flame. The surrounding field of blue alludes to the surrounding ocean of the Southern Hemisphere, from which, in Dante’s vision, the mountain of Purgatory arises. Love enables Dante to overcome the challenge of the fire. And indeed, the central theme of the entire poem is the power of love.

By Gervase Rosser

Professor of Art History, Department of the History of Art

Dante: The Invention of Celebrity is at the Ashmolean Museum, Gallery 8 (free admission) until 9 January.

The Divine Comedy from Manuscript to Manga is at the Bodleian Library, Blackwell Hall (free admission) from 18 September to 17 November.

Gervase Rosser, Dante: The Invention of Celebrity (Ashmolean Publications) is available from the Ashmolean Museum shop, price £15.

Find out more about the Dante 2021 Season here.