Dante on Fame

In the future, everyone will be world-famous for five minutes.

Andy Warhol

Ours is an age of personality cults, of fashionistas, of instant and often unremarkable celebrities. Modern media have accelerated the construction of personal fame, which to a limited extent has also been democratised, as Andy Warhol anticipated. Early predictions of the demise of celebrity culture as a result of the Covid pandemic are proving to have been premature, while The X-Factor, successors to Big Brother, the persona of the Internet blogger and the Instagrammed selfie remain to the less rich and famous as means to reach out for recognition from our fellow human beings.

Yet our desires are not so original – it is only our arrogance that leads us to think them to be so – and these staples of our modern world have an origin which lies deep in the European cultural past. In fact, it was Dante’s Divine Comedy which, for the first time ever, dramatized the lives of ordinary people on a world stage, with full exposure of their failings. And by writing a poetic best-seller, Dante in turn became, himself, a celebrity. As the man who had been to Hell, who told truth to tyrants and exposed the corruption of popes, and whose own love-story with Beatrice was the ultimate romance epic, Dante himself acquired the status of an icon. For – again – the very first time, an individual of no particular status became an international poster-boy for justice, liberty, and love. The exhibition to celebrate the seventh centenary of the man today honoured as l’altissimo poeta, ‘the loftiest poet’, which is due to open at the Ashmolean Museum in September 2021, is entitled ‘Dante and the Invention of Celebrity’.

Far older yet than Dante, of course, was Fame: that fickle, god-like power which makes or destroys reputation. Classical poetry and public statues constructed the glory of male heroes of the battlefield (Hector) or the intellect (Plato). At the same time, the ancients were aware of the corrosive effects of human forgetfulness or, worse, rumour, which could mar the standing of the most glorious. Dido and Aeneas, in Book IV of Virgil’s Aeneid, suffer the slander of rumour, described as a horrible ‘monster’ which spreads salacious stories in a ‘mixture of fact and fiction’. Virgil’s younger contemporary Ovid, in Book XII of his Metamorphoses, imagined the House of Rumour to be located in the centre of the world, where all tales could be heard, elaborated and redistributed with destructive consequences. In the house, ‘rumours mingle in their thousands, the false with the true’. There has always been ‘fake news’, and the fragility of worldly reputation is something which has been taken for granted from ancient times.

Medieval Christianity complicated but did not altogether banish fame. Saint Augustine patronized pagans who hoped for the hollow reward of earthly fame, while Christians enjoyed the prospect of eternal glory in heaven. Yet Dante, who like Augustine had read the Roman poets, developed a more complex relationship with celebrity in the world. One potent classical idea to which Dante remained closely wedded was that of the poet as a prophet and guarantor of fame. Virgil achieved this for Aeneas, and in the process ensured his own eternal glory. When the character of Virgil in the Comedy relates to Dante how he was visited by Beatrice, he reports that she addressed him with the words: ‘O Mantuan soul, the soul of courtesy, / Whose glory is still current in the world’* (Inferno II 58-60). Ovid had concluded the Metamorphoses, which Dante knew as well as he did the Aeneid, with the words: ‘If truth at all / Is stablished by poetic prophecy, / My fame shall live to all eternity.’

With these thoughts in mind, Dante found it impossible to believe that the great poets of Antiquity, because of their blameless ignorance of Christianity, could not be touched by the grace of the Christian God. Hence his inspired creation, in Limbo just outside the bounds of Hell proper, of the Noble Castle, the tranquil home of the ancient sages. When the pilgrim Dante asks Virgil to explain this, he is told that their virtuous reputation in the world has earned them this privilege as a divine grace: ‘Their honourable name, / Still echoing throughout the world above, / Wins grace in heaven and thus advances them’ (Inferno IV 76-78).

Dante with Virgil, Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan outside Noble Castle. Bodleian Library, MS Holkham misc.48 (mid-14th century, Naples?).

As the reader follows the pilgrim Dante on his journey through the other world, it turns out that the entire Divine Comedy is a vast hall of fame, in which a host of characters, ranging from the most eminent to the very obscure, are made famous by Dante’s poetry. The lovers, Paolo and Francesca (Inferno V), Ciacco the glutton (Inferno VI), the smiling and gentle Piccarda (Paradiso III) and many others, who would otherwise remain unknown to us, live on through the lines of the Comedy. We are distracted from the poet Dante’s responsibility for the creation of their fame by the internal morality of the poem, in the course of which the pilgrim called Dante is educated to recognize the emptiness of worldly honour in the absence of divine grace.

The one thing which preoccupies all of the shades Dante encounters in Hell is the state of their reputation on earth: this futile concern is all that remains to them. Characteristic is Ciacco, who though condemned for eternity to the stinking morass of the third circle under continuous rain and hail, is still moved to urge Dante to remind his fellow Florentines of him on his return (Inferno VI 89). As he falls back into the mud, we realise that the natural condition of Hell is, in fact, silence; that the only reason we hear of the souls there is that the poet Dante has spoken for them. The suicide Pier delle Vigne is persuaded to tell his tale when Virgil assures him that Dante will be able to ‘Restore you to your worldly reputation’ (Inferno XIII 53). In the burning sands of the sodomites, Dante meets three other Florentines who expect that he will recognize them because of their ‘fame’ (Inferno XVI 31). Dante is not unpleased to see them, but the good reputation which they enjoyed as honourable citizens has not sufficed to earn them salvation; and the pilgrim passes on. In the lower depths of Hell, where the worst offences are punished, the sinners are reluctant to identify themselves for fear Dante may worsen their image in the world. The thief Vanni Fucci, who robbed a church and laid the blame on others, declares that he is more tormented than at his own death by being recognized and made to tell his story to Dante (Inferno XXIV 133-35). Guido da Montefeltro, among the false counsellors, only concedes to speak of his deathly advice to the pope because he cannot believe that his interlocutor will return to the world (Inferno XXVII 61-66). Wedged in the perpetual ice of the traitors in Cocytus, and taking a brief respite from gnawing on the neck of his bitter enemy the Archbishop Ruggiero of Pisa, Count Ugolino hopes, by telling his story to Dante, that the archbishop’s ‘infamy’ in the world may be increased (Inferno XXXIII 8).

So even while the pilgrim in the vision is made to understand that the fixation shared by Hell’s population with fame and reputation is sterile, Dante the poet conjures into our enduring memories – seven centuries on – the undying images of those same sinners. Dante has it both ways, and he continues to do so in the higher realms of the other world. On the mountain of Purgatory, the lowermost and weightiest of the sins being purged is that of pride. The sinners are bowed low under the weight of great rocks which, in expiation of the offence which they have repented, they willingly carry until the due time for their release. One of these is the illuminator Oderisi da Gubbio, who has put behind him the pride he once took in his reputation. ‘Vanity of vanities is man’s renown!’ he exclaims, going on to moralise about vainglory:

Non è il mondan romore altro che un fiato

di vento, che or vien quinci ed or vien quindi,

e muta nome, perchè muta lato. Purgatorio XI 100-102

(A changing gust of wind is worldly fame, / Now here, now there – and what we call it varies / According to the quarter it blows from.)

Worldly glory is transient: the message seems clear. Yet in the line immediately preceding this warning, Oderisi, referring to the poets Guido Guinizelli and Guido Cavalcanti, older contemporaries of Dante, has just prophesied that ‘now perhaps / There’s one who’ll drive them both out of the nest’: an unequivocal allusion to the coming fame of Dante himself. In Paradiso Dante continues without embarrassment to invoke the Muse of poetry, ‘che gl’ingegni / fai gloriosi, e rendili longevi’ (‘who make great minds / Illustrious, and render them immortal’) (Paradiso XVIII 82-83). There is no doubt of Dante’s self-awareness of his place in a lineage of great poets, as he indicated at the outset of the Comedy when the five noble poets and seers of Antiquity ‘mi fecer della loro schiera, / si ch’io fui sesto tra cotanto senno’ (‘they invited me to join their circle: / I was the sixth, with such great minds as they’) (Inferno IV 101-2; see the picture above).

It becomes clear that, in Dante’s eyes, the right kind of fame can in fact do good in the world. So it is with the troubadour poet and later Cistercian monk, Fulques of Marseille, encountered in Paradise. Fulques is first pointed out, in the heavenly circle of Venus, by another soul who says of him that he still enjoys ‘great fame’ in the world, and will continue to do so for another five centuries. The same soul asks a rhetorical question: ‘So should not men seek excellence / Until a second life [sc. after death] succeeds the first?’ (Paradiso IX 39-42). And in the circle of Mars, the poet’s own ancestor, Cacciaguida, foretells that ‘s’infutura la tua vita’ (‘your life will last out’) far beyond even the punishment in Hell which would be imposed on his fellow-Florentines who had exiled him (Paradiso XVII 98-99). So often does he return to the subject, that it is clear that Dante was anything but indifferent to fame.

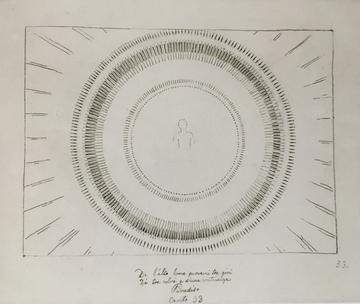

Dante reconfigured fame to become a means of salvation: his own and that of others. The notion of fame itself was old, but his particular combination of Roman glory and Christian morality was distinctive, striking a balance between this-worldly and transcendent aims which would resonate far into the future. Moreover, his radically inclusive vision of human community meant that, in place of the narrow elites of pagan heroes and Christian martyrs conventionally held up as examples of good living, the Comedy presented an infinitely diverse cast of men and women, each realised by the poet in their unique individuality. When the pilgrim, at the final climax of his vision, sees the Holy Trinity in the form of three concentric circles of light, he also recognises within that circling light a reflection, ‘come lume riflesso…pinta della nostra effige’ (‘a light that was reflected…painted with the Image of Mankind’: an allusion both to the incarnate Christ and to humanity made in God’s image) (Paradiso XXXIII 131). In that moment, the visionary realises that humankind in general, and every individual, is a glorious reflection of divinity, and truly deserving of the lasting fame which only the poet can convey.

John Flaxman, The Vision of God (Paradiso XXXIII). Compositions by John Flaxman, Sculptor, R.A., from the Divine Poem of Dante Alighieri: containing Hell, Purgatory and Paradise (London, 1807). From the copy in the library of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

*English versions of the Comedy are from the translation by J.G. Nichols, The Divine Comedy (Alma Books, 2012), with permission.