Fake Gold? Tumbaga

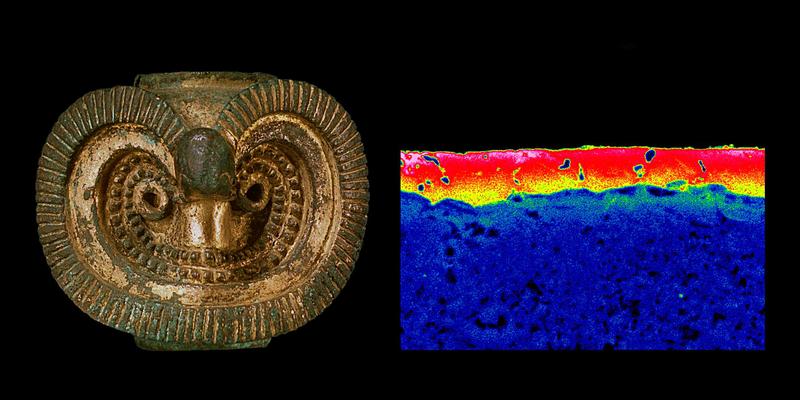

Pectoral depicting a schematic anthropo-zoomorphic figure made from tumbaga. AD 700 - 1600, Late Quimbaya, Colombia. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum's Thomas A. Cummins and Laura Perucchetti tell us about tumbaga.

"Gold is the most precious of all commodities: gold constitutes treasure, and he who possesses it has all he needs in this world.” (1)

In this one quote, Christopher Columbus captured the prevailing attitude towards gold of almost every European monarch and empire in the 16th Century (2). It was with this desire for gold that conquistadors like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizzaro attempted to seize the wealth of the Americas for themselves and the Spanish crown (3). However, for many looking to find their own riches in the Americas, this dream soon soured. With the fabled gold mines of regions eluding them, many conquistadors resorted to looting and destroying gold pieces held by the indigenous people (4). But further disappointment awaited, as once these objects were melted down, what had appeared to be pure gold, turned out to be nothing more than an alloy, with as little as 20% gold in some cases.

Today this alloy is known as tumbaga, in reference to pre-Columbian objects made using a combination of gold, silver and/or copper (Fig 1). Depletion of the copper and silver through the application of naturally corrosive minerals and processes, resulted in surfaces that were enriched in gold. Careful burnishing eliminated the porosity caused by the depletion (Fig. 2), producing a smooth and shining golden lustre.

Fig 2. SEM detail of a depletion-gilded figure. This is a small unburnished area showing what the surface looks like before it is burnished to achieve the shining gold finish. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 1. Pendant in the form of a human-headed bird made from tumbaga. Cauca, Colombia. AD 900-1600. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Are pieces made from tumbaga ‘fake’ gold? Of course not. Were the Spanish fooled into thinking it was ‘real’ gold? Not deliberately, no. Both groups were approaching the making and value of gold from two very different world views. As such, the story of tumbaga is one of the colliding of cultures, their values, their manufacturing, and their relationships with materiality.

The word tumbaga does not originate from any of the languages of the Americas: rather it is a South Asian word, originally meaning “copper”. Likely introduced into the lexicon of metallurgy of the Americas via “the Manila Galleon”, a series of voyages between Acapulco, Mexico, and Manila from the 16th to18th century, tumbaga came to describe a “gold alloy”, that is not naturally occurring. In South America, gold is found in veins and placers in almost pure form, often in association with silver and/or platinum. This means that the copper-gold alloy that characterises the composition of many tumbaga objects can only be humanmade .

It is also important to acknowledge that tumbaga is an umbrella term that encompasses a tremendous number of different techniques, used by many groups across the Americas to enrich the surface of objects in gold, silver, or a combination of the two. This shows an incredible range of skills and breadth of talent in the art of metalsmithing. Only recently has scientific investigation of these objects allowed us to understand the complexity of the various techniques, and traces of them can be dated as far back as 3000 years ago (5-6).

Some examples of processes that come under the tumbaga term include;

- The application of gold foil to objects of another metal, despite natural inclusions such as platinum, making it extremely difficult to hammer the gold to foil thickness (7).

- Fusion gilding, developed by the Tumaco-La Toilta culture set in the coastal region between present day Ecuador and Colombia (300BCE-800CE) and sees copper objects coated in gold by dipping them in molten gold-copper alloy (8) (Fig 3).

- Electrochemical replacement, discovered by the Moche culture of Peru’s desert north coast (100-800CE) (7).

- Silver surface enrichment in copper-silver sheet metal, by depletion of copper through long series of hammering and reheating the metal (7).

Fig 3. Magnified cross section with SEM false colouring of the fusion guilted surface of this copper owl mace head. The red layer shows the gold guiding. The blue is the copper underneath. Moche, Peru. AD 1 – 700. © Courtesy of Susan La Niece

However, by all accounts, gold enrichment through depletion with the use of salts was the most widespread technique among cultures of the Americas, both for metal sheets and for cast objects (7-9).

When talking about gold items from South America, we must put aside the conventional attitudes held by 16th century Europeans. Many indigenous groups did not consider gold to be a source of wealth, but rather held the belief it was charged with symbolic and religious values. Displays of religious and social power, known as conspicuous consumption, were the main reasons for gold consumption. For example, the Spaniards reported the Inca royal family claimed to be descendants of the sun and the moon, and that gold was the “sweat of the sun” and silver the “tears of the moon” (7). Therefore, the most sought quality was the appearance of the gold (and silver) colour, rather than the value of the metal.

For many groups in the Americas, gold was seen as a means of connecting with the supernatural and displaying rank and authority. Its immunity to corrosion made it an important symbol of enduring power and immortality and its composition in regalis such as masks, collars, pectorals, and other ornaments, allowed light to dance off its surface, creating dramatic visuals to portray the rulers power as well as their proximity to the divine (3).

Fig 4. A cast bell made from gold and copper. Tairona, Colombia. AD 900 – 1600. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The visual value of these metals was not the only important factor for indigenous cultures though. Gold and silver were also widely used in the production of musical instruments, in particular bells (Fig 4). Different alloys and compositions of metals were used to obtain different sounds (10). It is therefore possible that the composition of the core metal was determined to obtain a particular pitch when the object was struck.

On the other hand, in Europe, gold was (and is) valued for its materiality. Conspicuous consumption of gold objects is certainly true in Western cultures, for example, most of the patens and chalices used in Christian masses are made of gold or silver, but gold has been also used as currency for millennia. As such, its purity is more important than its appearance and many forgery activities aim to produce objects that mimic a golden appearance while actually being composed of "base metals" such as bronze or copper.

It was this European appetite for gold as a base material that many indigenous groups in the Americas found perplexing, as, there are hints that to them, its raw form had no real value. This difference is summed up by a Panamanian chief’s son, who, puzzled by the Spaniards melting the fine jewellery and other metalworks into ingots, pointed out that raw gold is no more valuable than a lump of clay, it is only once it is made into something aesthetically pleasing or useful that it becomes valuable (11). It is also this lust that led to the loss of countless indigenous lives, as well as the destruction of countless historic treasures and the stories they might tell.

References

- Columbus, C. 1847. Select Letters of Christopher Columbus. P. 196. London: Hakluyt Society

- Cartwright, M. 2022. The Gold of the Conquistadors. World History Encyclopedia, 25 Jul 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2045/the-gold-of-the-conquistadors/.

- Jones, J. 2000. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Fleming, Stuart J. 1999. "Confounding the Conquistadors: Tumbaga’s Spurious Luster." Expedition Magazine 41, no. 2 (July 1999).

- Blust, R., 1992. Tumbaga in Southeast Asia and South America. Anthropos 87, 443–457.

- Scott, D.A., 2011. The La Tolita—Tumaco Culture: Master Metalsmiths in Gold and Platinum. Latin American Antiquity 22, 65–95. https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.22.1.65.

- Bray, W., 1993. 16 - Techniques of gilding and surface-enrichment in pre-Hispanic American metallurgy, in: Niece, S.L., Craddock, P. (Eds.), Metal Plating and Patination. Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-1611-9.50020-0

- Lechtman, H., 1984. Pre-Columbian Surface Metallurgy. Scientific American 250, 56–63.

- Perea, A., 2018. On Quimaya goldwork (Colombia), lost wax casting and ritual practice in America and Europe, in: Armada, X.-L., Murillo Barroso, M., Charlton, M. (Eds.), Metals, Minds and Mobility: Integrating Scientific Data with Archaeological Theory. Oxbow, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 53–66

- Gudemos, M., 2016. Cuando los Mâmas ‘danzaban como tigres’. La estética Sonora Quimbaya., in: Perea, A., Casanova, A.V., Usillos, A.G. (Eds.), El Tesoro Quimbaya. CSIC - Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Madrid, pp. 155–169.

- Schrimpff, M (ed) 2005. Calima and Malagana: Art and Archaeology in Southwestern Colombia. Pro Calima Foundation, Colombia.