Fluvial Journeys: The Musical Possibilities of a River

As Patrick McCully comments in his book, Silenced Rivers (2001), ‘the great milestones of human history took place by the banks of rivers’. It is no surprise, then, that they occupy an important position in, not only geographical, but cultural histories. This blog post hopes to introduce some musical examples which demonstrate the importance of rivers over recent musical history, before introducing their role in my HCP–funded project: Pixelating the River.

One of the best-known examples of water in music, George Frederic Handel’s Water Music (1717), is a set of three orchestral suites written at the request of King George I, who wanted a concert on the River Thames. Two barges, one filled with royals and aristocrats, and another with musicians, travelled down the river towards Chelsea as the public flocked to the banks to listen. The significance of this piece is not so much that it ‘sounds’ like the River Thames (although one might read the dotted rhythms of the ‘Air’ movement as the gentle swaying of boats on the water) but rather the significance of the context. Many studies suggest that this concert was a publicity-boosting spectacle organised by George I, who suffered from unpopularity due to his German origins. Indeed, many preferred his son, George II, who did not attend the concert. Water Music’s eccentric performative grandeur imbues it with a specific time and place; it evokes the images of the spectacle when one listens – images that are derived from the River Thames. You can listen to the ‘Air’ here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BKxEIhPCrUQ

Figure 1. Handel (left) and King George I on the River Thames, 17 July 1717; painting by Edouard Hamman

Another example of how a river can evoke a time and place can be seen in Johann Strauss II’s An der schönen, blauen Donau (On the Beautiful Blue Danube, or The Blue Danube) (1866). Probably recognised as the most famous collection of waltz–tunes of all time, becoming the unofficial national anthem of Austria, The Blue Danube is evocative of Austrian waltz culture during the 19th century, but written during a period of national crisis. 1866 marked the end of the Seven Weeks’ War between Prussia and Austria, with Prussia claiming victory. The low morale and post-war economic depression led to calls for Strauss to compose something uplifting for Vienna, and thus The Blue Danube was written. This piece was famously used in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, accompanying images of humanity’s first attempts at space travel, providing a jarring contextual dissonance between hearing something indicative of the Austro-German musical tradition, whilst seeing something indicative of the future. Perhaps through a reading of the ‘river’ as a contextual device, one can understand the significance of this combination. Rivers are, by their nature, transitional; they flow towards a single trajectory through their current. Humanity’s leap from Earth to space is mirrored in the transitional nature of the river, embodied by the anachronistic sound of The Blue Danube – itself emblematic of a country in crisis. You can watch this scene here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ZoSYsNADtY

Figure 2. Theo Zasche ‘Johann Strauss II at the Court Ball’ (1888)

Figure 3. Theatrical poster for ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

Both Handel and Strauss use rivers as symbolic of their nations. Arguably, Strauss’s piece has retained this national connection much more enduringly, with The Blue Danube being a permanent fixture of Viennese New Year celebrations.

But how can rivers be used in a more poetic, or metaphorical way? In Schubert’s seminal song cycle Winterreise (1827), there is a movement entitled ‘Auf Dem Flusse’ (‘By the River’). In this song, the protagonist, ‘the Wanderer’, revisits a river that has since frozen over. He scratches the name of his beloved on the surface of the ice, and finally equates the river to his heart in the ‘seething torrent’ (‘reissend schwillt’) beneath its surface. Here, the river acts as a metaphor for forsaken love in the changed state of the water (turning to ice) as well as the absence of any reflection as a result of this change. David Lewin (2006) notes of the temporal aspect of this metaphor, ‘[t]he subglacial flow of the stream, if existent, is a portent linking its future with its past’. The altered function of the river is explored and linked to personal circumstance and emotional turmoil. The music is characterised by staccato piano writing, alongside lyrical vocal writing, perhaps signifying these two ‘states’ of the river. The latter part of the song builds in intensity, as the Wanderer becomes introspective, yet hopeful that this torrent does indeed ‘exist’ below the river’s frozen surface. Schubert’s exploration of a river is deeply reflective and metaphorical in the truest sense of Romanticism, and acts as a personal journey through complex emotions. You can listen to this song here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKCeKTdgXXI

A metaphor of transition using a river is also shown through Harrison Birtwistle’s The Mask of Orpheus (1986), which was (divisively) revived at the English National Opera in 2019. Following the orphic myth (which Birtwistle has used often e.g. Nenia (1970), The Corridor (2009)), The Mask of Orpheus is a stunning work which emphasizes non-linear plot structure and dazzling electronic sounds. The opening of Act II sees Orpheus travel through seventeen arches to reach the underworld, crossing the River Styx with Charon (the ferryman of the dead). The first arch is symbolically called ‘Countryside’, with Orpheus singing about the ‘rocks, trees, rivers’ etc. which he can see. The River Styx is a transitional narrative device in the Orpheus myth, treated here by Birtwistle in a more complex way; it is not simply about crossing the river to reach Eurydice, but about memories, the present, and the future. Having said this, the sheer complexity of Birtwistle’s narrative structure finds respite in this directed journey through the seventeen arches that consists of almost the entirety of Act II. Somewhat surprisingly, this journey is actually revealed to be a dream, thus questioning the narrative and transitional properties of the river in Birtwistle’s opera, adding to the sophisticated non-linear structure after all. You can listen to the first arch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ab4Q3G-Jqko

Figure 4. The Mask of Orpheus (Composer Harrison Birtwistle & Jean Rigby as Eurydice), © Zoe Dominic

Figure 5. ENO ‘The Mask of Orpheus’ 2019, William Morgan, Peter Hoare, Simon Wilding, David Ireland, © Alastair Muir

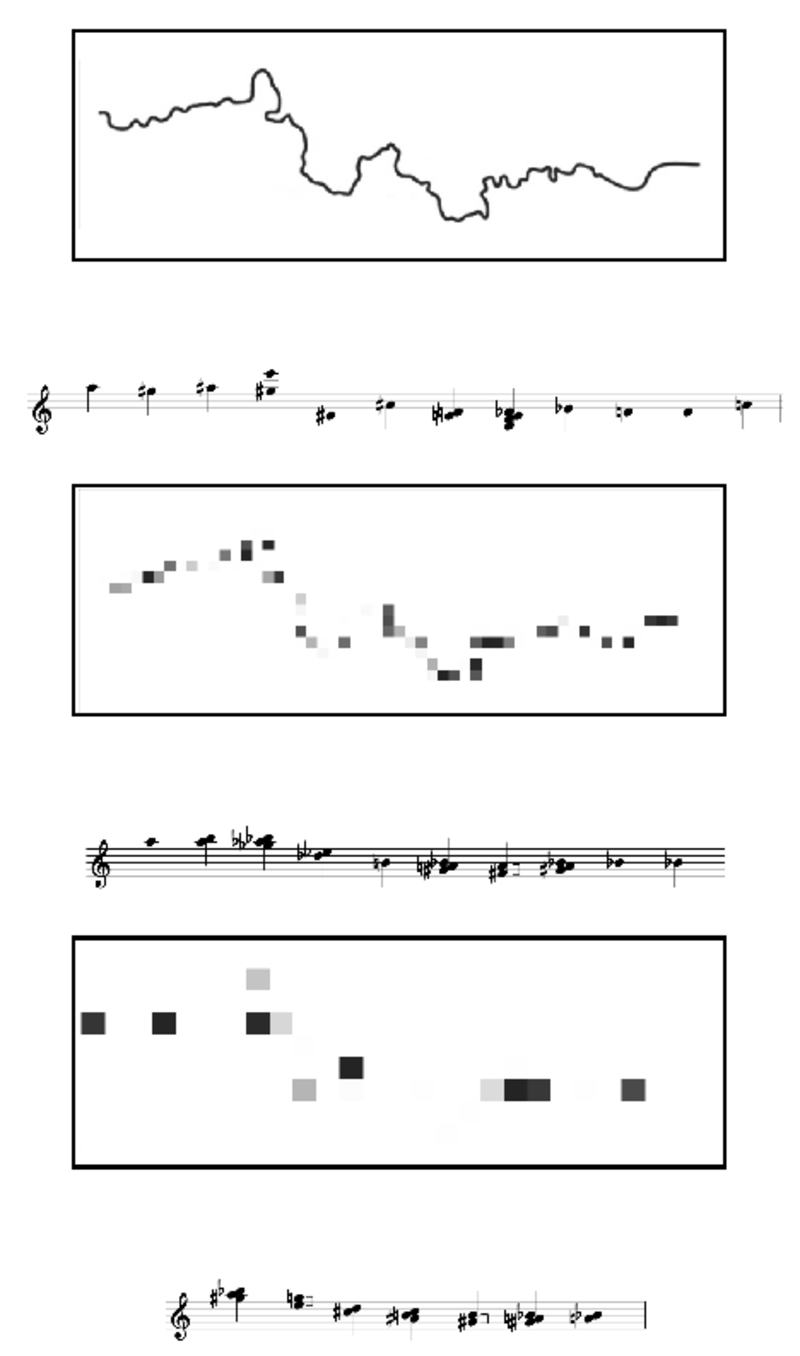

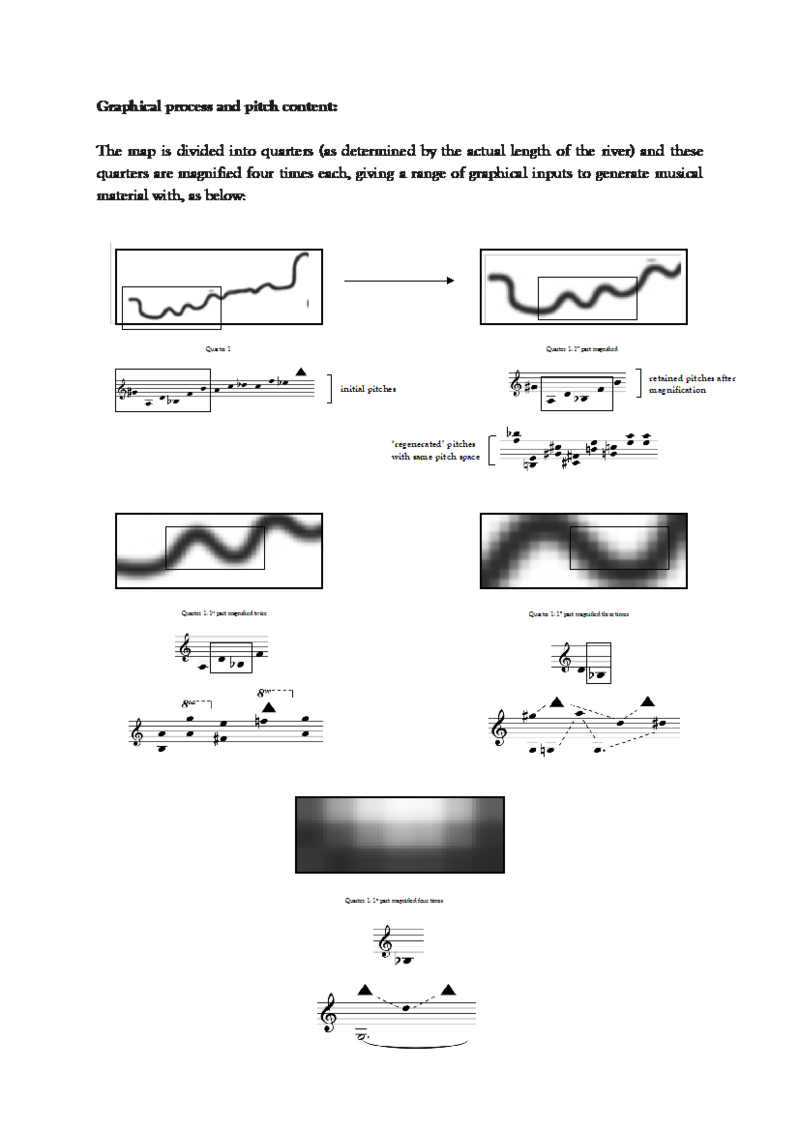

Linking back to the River Thames is where my HCP project is situated. My composition aims to use a map of the River Thames as a functional generator of musical material, rather than just as metaphor or extra-musical spectacle. The shape of the river, its meanders and straights, will impact specific compositional details on both the micro and macro level. It will utilise multiple methods of graphical composition in order to create a musical representation that holds true to the spatial layout of the river. Thus, the river metaphor can be heightened and rendered more specific – something I call a ‘graphical ekphrasis’ (an extension of Siglind Bruhn’s ‘musical ekphrasis’ (2000); see also my article, ‘Graphical Ekphrasis: Translating Graphical Spaces into Music’, coming out in September in Question). I also believe that these methods of composition can allow for a heightened engagement with non-specialist audiences; directing them to specific processes which can be rationalized through a near-universal understanding of visual graphics. Another aspect of this project is applying the visual phenomenon of pixelation to these graphical inputs, and exploring the musical implications of this. Musical pixelation is something I am very interested at the moment, and I will soon be sharing my work, Pixelation Variations (2020) for organ, which also uses the River Thames as a graphic input. The piece was written for Daniel Mathieson and will be premiered in the coming months. A sneak preview, of the first movement, has kindly been recorded by Daniel, and can be heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gzghj3W9BuA

Figure 6. Graphic and pitch material from movements I, III, and VI of 'Pixelation Variations' (2020)

I am thrilled to be working with the Kreutzer Quartet on this project and, as part of the final piece, I am composing solo pieces for each instrument of the quartet which explore a particular part of the river graphic, entitled Vignettes of a Pixelated River. The first is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mMnoEFrjHhE&feature=emb_logo

Figure 7. Harmonic material for ‘Vignettes of a Pixelated River: No. 1’ for solo violin

This event will take place in Hilary Term 2021, and will feature a lecture on graphical composition and ekphrasis, followed by a recital of my own work, alongside Anne Boyd’s String Quartet No. 2, ‘Play on the Water’ (1973). I look forward to sharing more information on this project as it develops, and would like to add my thanks to the HCP Fund for supporting it.

Thomas Metcalf

DPhil in Music

Worcester College, Oxford

July 2020

Also see the 'Pixelating the River' project website, part of the TORCH Humanities Cultural Programme.