Graphic Novels, Comics and Human Rights

A new blog post from the Fiction and Human Rights Network

The Fiction and Human Rights Network Blog

Posted by: Dominic Davies, 7th March 2016

Graphic Novels, Comics and Human Rights

Comics, comix, graphic literature; a genre that, though originating in the U.S. in the 1930s and perhaps still more often than not associated with the superheroes of Marvel and D.C., has witnessed a surge in formal innovations in recent years that have expanded its boundaries and played, quite literally, with its borders.

Early comics tended to stick to basic grids and square or rectangular panels, a rigid framework that has been bent and transgressed in creative and exciting ways by numerous authors and artists in the last few decades. Innovative authors such as Alan Moore and Art Spiegelman departed from these short, simple panel sequences to create increasingly labyrinthine and complex compilations of images, woven into novel-length narratives and non-fictional reportage.

This increasing versatility has resulted in an explosion in the production of graphic literature and given rise to its application to all sorts of genres and topics across the globe. If in their more recent incarnations comics have come to be known as graphic novels, it is worth considering that this renaming might in fact serve to legitimise, if not sanitise, the study and consumption of what was once dismissed as a “low” and subversive cultural medium by academics and middle class readerships. Nevertheless, this co-option is surely still symptomatic of the increasing virility, potency and adaptability of a form that can tell us something about life in the twenty-first century. Undoubtedly, then, we are entering the era of the comic.

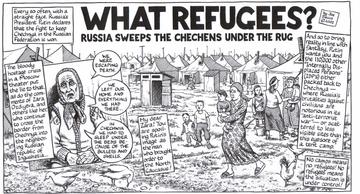

Of particular interest for the TORCH Network, “Fiction and Human Rights”, is undoubtedly the groundbreaking work of comics artist Joe Sacco which, in the 1990s and early 2000s, documented atrocities, testimonies and histories in conflict zones from Gaza to Sarajevo, and that has since pioneered a whole new genre that in the last decade has come to be known as “comics journalism”. Comics more broadly have almost always been historically associated with traditions of political satire and subversive activism, and have often been an “underground” artistic practice, written, drawn and published by networks of anti-establishment artists and consumed by radical readerships.

This tradition of holding power to account has made them a fertile form for critiquing human rights abuses the world over. Indeed, since Sacco, and facilitated by the coterminous rise of the internet that reduces printing and publishing costs for aspiring artists, comics are now being used to document, analyse and protest against some of the greatest human rights crises of the twenty-first century.

Consider the example of the PositiveNegatives Project, which combines in-depth ethnographic research with illustration and photography to produce individual, humanised stories that educate readers about the realities of all kinds of conflicts and traumatic experience. Most recently, they have addressed the plight of Syrians leaving war-torn cities to seek refuge in Europe.

Reproduced in The Guardian and Aftenposten newspapers and exhibited at the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo at the end of 2015, these comics used the cross-national potential of the form—it is, after all, primarily comprised of icons, images and only short pieces of English text, and is decipherable to a wide readership—to generate empathy through education in its various readerships. The “interactive” version of these comics facilitate a much-needed empathetic solidarity between the Syrian refugee and readers in host populations in Europe that allows them to recognise both their humanity and their rights.

Elsewhere, the self-labelled “graphic non-fictionalist”, Erik Thurman, has used the online comics form to raise awareness about topics as various as the human rights abuses perpetrated against migrant workers in Qatar building the stadiums for the 2022 Fifa World Cup and the government censorship and oppression of protest movements in Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, Josh Neufeld has produced a long-form documentary comic entitled A.D.: New Orleans, After the Deluge, which visualises the traumatic experiences of victims of Hurricane Katrina back in 2005, and Jess Rufflinson has contributed a series of panels to online comic forum The Nib called Voices From Nepal, which highlight the ramifications of the recent earthquakes in Nepal for its inhabitants in their own words. These comic artists borrow Sacco’s journalistic technique by quoting these victims directly in order to document the slower forms of violence that take place after a disaster has disappeared from the headlines of mainstream media.

Whether there is a specifically historic-formal connection between the comics form and issues of human rights, akin to that identified by Joe Slaughter between Enlightenment Human Rights discourse and the bildungsroman narrative, is yet to be seen. If there is a connection of this kind, however, then it is, I would argue, surely a positive one.

These comics, which address issues from all over the globe, do not propagate Western-centric notions of human rights or perpetuate problematic and hypocritical engagements with these philosophies. Instead, they draw on comics’ radical roots and politically subversive traditions to raise awareness about human rights abuses through their powerfully visual, and thus widely accessible, formal strategies.

Dominic Davies is a British Academy Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Faculty of English.