I say viennas, you say vy-eeners: visibility and queerness in white camp drag from Atlanta to South Africa.

Blog post by Ruth Ramsden-Karelse

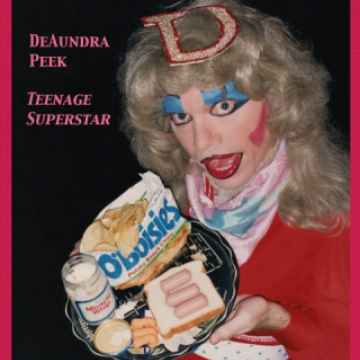

As part of our ongoing series of blogs, we’re delighted to share DPhil candidate and Queer Studies Network co-convener Ruth Ramsden-Karelse’s response to Professor Molly McGehee’s recent talk at TORCH. Molly discussed the performances of Atlantan drag queen, public-access television star and connoisseur of tinned ‘vienna’ sausages DeAundra Peek (alias Rosser Shymanski) during the 1980s and 1990s, ultimately arguing that Shymanski’s performances ‘did not expand southernness so much as produce an expansive queerness.’ In her response, delivered on 15 November 2017, Ruth considers the function of visibility in South African Pieter-Dirk Uys’s performances as Evita Bezuidenhout alongside Molly’s analysis of Shymanski’s performances as DeAundra.

Keywords: Drag Performance, Visibility, Queerness, South Africa, Whiteness

I want to start off by saying that while I was, of course, excited to read Molly’s paper, I hadn’t expected to be quite so excited by the very first word of its title: ‘viennas’. Growing up in South Africa, where we used the term often, and then in England, where I’ve never heard the word used by an English person, I had assumed that calling processed and smoked sausages ‘viennas’ was unique to that peculiar South African dialect of English, in which we call trainers ‘tackies’, we call felt tips ‘kokies’, and – seemingly most confusingly to non-South Africans – we call traffic lights ‘robots’. However, with the first word of her title, Molly taught me that ‘viennas’ is a term that we South Africans have, in fact, borrowed from the original and still best bastardisers of the English language: the Americans.

So, I ventured on with Molly’s paper, with a newly-prompted interest in the relationship between the specific Atlantan ‘queer ecology’ Molly writes about, and the divergent South African contexts which I write about – in which, of course, class, race, gender and sexuality operate in different ways. Molly’s analysis of Rosser Shymanski’s performances as offering solace and escape to the gay community during the era of the AIDS crisis particularly spoke to me. I found the way she works through possible functions of queer visibility a valuable model – one which has helped me think through the effects of the work of a particular South African drag queen.

I found myself thinking, as I read about Shymanski’s performances, of Pieter Dirk-Uys, a South African performer whose best-loved character, the self-proclaimed ‘most famous white woman in South Africa,’ rose to prominence during the same years DeAundra Peek graced public access channels in Atlanta. Uys initially developed the persona of an Afrikaner matron, Evita Bezuidenhout (who he describes as a cross between Imelda Marcos and Miss Piggy) as the ‘author’ of a column in the Sunday Express, a South African newspaper he was writing for during the 1970s, as a ‘means of getting information across that wasn’t allowed to be written about,’ by framing it as high society gossip (Lieberfeld and Uys, 65). In her newspaper column, and later out of it, Evita boldly declared the unspoken prejudices and principles of apartheid: for example, ‘Democracy is too good to share with everyone!’ and ‘Hypocrisy is the Vaseline of political intercourse!’ Uys styled Evita as Ambassador to (the fictitious Republic of) Bapetikosweti, and censors ignored the ironic framing of her rightist (and racist) outrageous opinions.

Before long, Uys went one step further and started dressing up as Evita for press photos. In 1981, Evita appeared on stage as part of Uys’s one-man review Adapt or Dye. At this time, it was illegal in South Africa for men to wear women’s clothing. Apartheid thrived on moral panic, and drag had been fodder for a particular bout of moral panic which culminated in 1969 in the Prohibition of Disguises Act 16, which criminalised men dressed in ‘female’ clothing, and resulted in gay men of all races increasingly being charged with ‘masquerading as women in public.’ Before inventing the character Evita, Uys had struggled through a series of his plays being banned by government censors. In 1997, he recounted that when the state didn’t stop him from dressing as Evita, he thought, ‘what the hell, I can just go on from here!’ He added – ‘still to this day I use her to say things I can’t as me’ (Lieberfeld and Uys, 66).

Although Evita and DeAundra were conceived for different purposes, they fulfilled some similar functions. In an interview last year, Shymanski said of his performances, ‘We did commentary on social issues disguised as improvisational comedy, and we seemed to hit a nerve with a lot of people!’ (Walker and Shymanski) While Deaundra, the sweet girl in thrift store dresses, challenged the figure of the southern belle, Evita challenged the figure of the affluent White Afrikaner woman, which, as Laurence Senelick points out in The Changing Room: Sex, Drag and Theatre, was ‘as venerated as the legendary belle had been in the Old South.’ (Senelick, 475) Both performances, to borrow Molly’s phrasing, ‘signal these identities as performed fictions’ – although Evita’s style of dress, make up and speech is markedly more naturalistic than DeAundra’s. Senelick explains that by adopting the guise of an affluent White Afrikaner woman, Uys had simultaneously besmirched that image and become invulnerable behind it: ‘to prosecute Evita would not only look absurd, it would seem to be an assault on Boer womanhood’ (Senelick, 475) – ‘boer’ here meaning traditional Afrikaner.

Evita proved so popular that in the run up to South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, she educated the public on voting laws. Following the election, Evita interviewed Nelson Mandela on national television. They discussed gender politics, Afrikaner fears, Mandela’s new life, and his hopes for a new South Africa. Mandela reciprocated Evita’s playful flirting, telling her how ‘beautiful’ she was. Evita told Mandela that she had ‘two little grandchildren, from my daughter Billie-Jean, and one little grandchild is called Nelson Ignatius,’ and they arranged for her to bring him ‘real Afrikaans bobotie’ (a traditional South African curried mince dish topped with egg). At the end of the interview, Mandela told Evita that she was his hero. Following this success, Evita starred in a television series, Funigalore, in which she interviewed other prominent South African politicans, many of whom had been listed as terrorists and ‘banned’ under apartheid.

Molly has discussed how drag performance, by Shymanski and others, became a resignification of Atlanta to the place it imagined itself to be. Similarly, in ‘A Queer Transition’, April Sizemore-Barber shows how Evita’s presence on television post-1994 made visible, and therefore real, the imagined new, inclusive South Africa, as she forced audiences to reorient their conceptions of race in relation to shifted gender dynamics. Both performers seem to have been ‘dragging’ their audiences into their own queer, imagined futures.

Both Uys and Shymanski are, of course, white men. Whiteness usually remains an unmarked category in scholarship on drag performance by white queens. However, Molly makes use of Ragan Rhyne’s essay ‘Racialising White Drag,’ in which Rhyne argues that drag performed by white queens must be understood as a performance of race as well as gender, and that camp drag, in which class is a ‘crucial category of performative femininity,’ might be a ‘key site through which whiteness is denaturalized and its power challenged’ (Rhyne, 182).

And, of course, both DeAundra and Evita love ‘viennas’! However, by the time I had watched a video of Shymanski perform as DeAundra, I realized that even though I had recognized the familiar spelling of the word ‘viennas’ in Molly’s title, in DeAundra Peek’s rural Georgian drawl, the word becomes ‘vy-eeners’. What on paper appeared to be familiar is, through performance, made markedly unfamiliar. This difference in pronunciation – ‘viennas’ vs ‘vy-eeners’ – operates as a metaphor for the difference between Shymanski and Uys’s modes of drag, with Shymanski’s pronunciation of the word cruder, more comedic, less apologetic.

To quote Molly, ‘the lovable DeAundra tries to embody the belle, through appearance and action,’ and yet her optimistic naivety – at times, her lovable gormlessness – contrasts with Evita’s strained affectations. DeAundra has all the youthful enthusiasm of an emerging counterpublic (and I’m using Michael Warner’s concept of the public and counterpublic here, to which Molly has referred) with her high energy demanding the energy of others to be buoyed up by, to shout over and to bounce off of. Evita, on the other hand, became increasingly less grotesque during ‘the transition’ years, as her opinions gradually shifted to generally fall in line with those of the new government.

During these years, Uys explicitly unpacked white baggage – the lies through which ‘liberal whites’ justified apartheid – and prompted his audiences to examine their own. Evita publicly grappled with shifts in power and comfort, signalling to white South Africans that their feelings of discomfort were to be expected; were part of the process. She thus modelled ‘good white South African behaviour’ during the transition: it was okay for them to be scared, but they had to actually make an effort to work through their fear and assimilate into the hazy glow of the Rainbow Nation. Sizemore-Barber argues that through this process, Evita Bezuidenhout has come to represent whiteness’s ‘potential for change, adaptation, and transformation’ (Sizemore-Barber, 198).

So, Tannie Evita (Auntie Evita), as she is now affectionately known in South Africa, has, like DeAundra Peek, provided ‘solace’ and ‘escape’ for a community: only this community was primarily white South Africa, and the persecution from which they wanted to escape was, in fact, attempts on the part of the majority to gradually level out the dilapidated playing field of apartheid. Molly argues that ‘DeAundra’s performances are actually not about expanding southernness as much as about producing an expansive queerness’ and ‘visibility’. By producing queerness, Shymanski was always ‘being a drag on’ nationalisms. Evita, on the other hand, seems to have increasingly dragged in service of the nation.

Uys certainly increased gay visibility in South Africa during the debate which led to the ANC’s inclusion of gender and sexuality-based rights in its constitution. The reason for Evita’s 1999 speech in South African parliament, as Uys later recounted, was that Frene Ginwala, then Parliamentary woman Speaker, wanted ’people’ (presumably LGBT people) ‘to know that Parliament [was] open to them,’ and that bringing Evita to parliament would evidence this (Lieberfeld and Uys, 63). Evita was thus utilised by the state to bring visibility to LGBT life in South Africa – albeit the white, privileged, theatrical gayness with which affluent South Africa is vastly more comfortable.

This narrative – of Uys bringing visibility to LGBT life – is further complicated by the fact that South Africans take Evita so literally: the press writes about Evita Bezuidenhout, or Tannie Evita – not Pieter-Dirk Uys. Uys himself has argued that politicians such as Pik Botha, stalwart of the whites-only Nationalist Party, were only willing to ‘appear arm-in-arm’ with Evita because they perceived her as a real woman. Uys has even written a ‘biography’ of Evita, complete with legitimising photographs and the incredible title, ‘A Part Hate, A Part Love’. Uys has stated that Evita is ‘so real that women recognize the femininity inside, and men forget that there’s a guy inside’ (Lieberfeld and Uys, 62). In light of the chilling fact that a girl born today in South Africa is more likely to be raped than to learn how to read, the fact that the ‘most famous white woman’ in the country is, in fact, a man can seem problematic.

The constitutional promise (which Evita helped usher in) of protection on the grounds of gender and sexuality remains unfulfilled by the reality of life in contemporary South Africa. In particular, black lesbians and trans people from deprived socioeconomic backgrounds have been failed by a thoroughly corrupt justice system which neglects to address systemic discrimination and widespread practices such as ‘corrective rape’. Earlier this year, in conversation with South African writer Nadia Davids about the student-led Rhodes Must Fall movement, Zethu Matebeni discussed the difference between the dominant narrative of gay South African history – which is white, but invisibly so – and the queer history which for her, starts with ‘a moment of intersectionality’ (Davids and Matebeni, 162-3). Mainstream gay activism in South Africa has, clearly, failed the masses.

So, I want to finish as I started – with the ‘viennas’. As Molly has shown us, the cheap tinned meat is used by Shymanski to signify DeAundra’s socioeconomic background: she lives in a trailer park, and her tacky taste forms the humorous basis for the recurrent skit in which she categorises ‘what’s high class and what ain’t’. In her performances, the emphasised phallicism of the ‘vienna’ sausages queer the southern, economically impoverished version of American whiteness being performed. Evita’s ‘vienna’ sausages, on the other hand, don’t come from a tin, and she doesn’t coat them in crushed up O’Boises chips and deep-fry them with a gang of misfit friends. In Evita’s snobbish Afrikaans-inflected English, the reference to the place Vienna in the name of the sausage codes a misguided white South African aspirational globalism.

While Shymanski has not, since 2009, publically performed as the eternally-16-year-old DeAundra, the ageing Evita has embraced the modern age and continues to upload weekly videos to YouTube. The videos, although still very enjoyable, evidence the difficulty of critiquing the corrupt, ineffectual shadow of the dream of the Rainbow Nation through a character who, decades ago, made the dream visible. There is, obviously, something to be said for visibility: for drag queens on screens, and for thinking through what they do. And what better time to do this than the present, as RuPaul’s Drag Race develops a cult-like following among even the straightest of audiences? It’s worth considering which audiences these queens on screens are trying to ‘drag’ along with themselves, and where to. What are their ‘queer imagined futures’?

So, Molly, thank you for your lecture, and for prompting me to begin to think through notions of visibility, the political efficacy of different forms of queerness, and the symbolism of the long-lost food from my childhood: ‘viennas’ – which, having watched Shymanski’s performances, I don’t think I’ll ever see in the same way again.

Bibliography:

Davids, Nadia and Zethu Matebeni. ‘Queer Politics and Intersectionality in South Africa.’ Safundi 18 No. 2 (2017): 161-167

Lieberfeld, Daniel and Pieter-Dirk Uys, ‘Crossing Apartheid Lines: An Interview.’ The Drama Review 41 No. 1 (1997): 61-71.

Rhyne, Ragan. ‘Racializing White Drag’ in The Drag Queen Anthology: The Absolutely Fabulous but Flawlessly Customary World of Female Impersonators, ed. Steven P. Schacht with Lisa Underwood, 181-194. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Senelick, Laurence. The Changing Room: Sex, Drag, and Theatre. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Sizemore-Barber, April. ‘A Queer Transition: Whiteness in the Prismatic, Post-Apartheid Drag Performances of Pieter-Dirk Uys and Steven Cohen.’ Theatre Journal 68 No. 2 (2016): 191-211.

Walker, John and Rosser Shymanski. ‘The (drag) queen of ’90s public-access TV is ready to reign once more.’ Splinter, 7 November 2016.

Warner, Michael. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books, 2002.

Ruth Ramsden-Karelse