Olive Gibbs (1918-1995)

Olive Frances Gibbs was a Labour politician and peace campaigner who was deeply committed to Oxford and the local area throughout her life.

Early life in Oxford

Olive was born on 17 February 1918 in St Thomas’s, a working-class parish just to the west of Oxford’s city centre. She was the daughter of Lazarus Cox and his wife, Mary Ann. Olive had one much older sibling, Syd. The family, though poor, lived quite comfortably compared with many in the parish.

Olive was baptised at St Thomas’s Church, and the Oxford High Church tradition was an important influence on her life. At the age of 2½, she was sent to St Thomas’s School on Osney Lane, her parents having persuaded the ‘formidable’ headmistress Miss Haithwaite that she was a nuisance at home and needed discipline. Later on, Olive won scholarships to the Oxford High School for Girls and Milham Ford School. Her father deemed the High School too ladylike for her and so she went to Milham Ford (whose buildings are now occupied by St Hilda’s College). Here she made several life-long friends and passed the school certificate in seven subjects–but also set a record of thirty-seven detentions.

In her autobiography, Olive described the domestic tyranny exercised by her spasmodically violent father, although later she came to see that he was caring in his own way, ambitious to give his two children better prospects in life. From his dictatorial behaviour she learned a lifelong considerateness and concern for the position of those like her browbeaten mother, and an abhorrence of corporal punishment and of violence of any kind.

She left school at the age of 16 and soon afterwards suffered a bout of bronchitis, and then pleurisy. Her godmother, Mother Anna Verena, the Mother Superior of St Thomas’s Convent, found her a post as an au pair in Nice, thinking that a change of scene would help Olive to recover her health, and also that she could learn French. She stayed with the family in Nice for 18 months and learnt fluent French.

Marriage and local politics

Olive returned to Oxford in March 1936, when she was eighteen. She wanted to follow her brother Syd into journalism, but was rejected by the chief reporter of the Oxford Mail because she was a woman, and so instead took a job as junior librarian at Oxford Central Library on St Aldates. Three years later she was promoted to librarian in charge of the four school library depots and stayed in this job until 1944. It was highly paid – £5 a week – but she had to give her father three quarters of this for her board and lodging.

Although her father didn’t allow her to use make up, smoke, or go to the pub, Olive did manage to have a good social life. At one dance in 1936 she met Edmund Gibbs, son of RWM Gibbs, a prominent left-wing Oxford councillor. They started going out, and every Sunday evening they would go to listen to the Communist activist Abe Lazarus speaking to crowds in St Giles. Abe had led a strike at the Pressed Steel Factory in Cowley in 1934, and a rent strike at the newly-built Florence Park estate in East Oxford. Olive recalled:

It didn’t matter what he was talking on – world starvation or the Civil War in Spain – he always reduced me to tears and every penny of my weekly pocket money found its way into his collecting box – my father used to give me a clout when I got home.

In September 1940 Olive and Edmund married. Their sons Andrew and Simon were born in 1944 and 1951.

Olive had long been an advocate of peace and democracy but her active involvement with local politics began in 1952 when she spearheaded a fight to save nursery schools (including her own former school, St Thomas’s) which were threatened with closure by the Tory-dominated city council. Invigorated by the partial success of the campaign, she joined the Labour Party and was elected councillor for the West Ward the following year, a position she held for thirty years. The frosty reception that her gender and left-wing views provoked from her fellow Labour councillors made her always welcoming to new political figures.

Worried about her children’s illnesses, unnerved by the challenges of public work in Oxford, and also, she believed, suffering a delayed reaction to her father’s bad treatment of her, Olive suffered a nervous breakdown in 1954. She recovered from this partly through working politically for the historian MRD Foot and partly through psychiatric treatment.

Olive’s long career in local government was distinguished by three major successful campaigns, in which she was prepared to work with whatever allies she could find, regardless of the party line. In 1958 she and her husband Edmund, who was also a city councillor, led a revolt of six Labour councillors on the majority Labour group against the proposal to build an inner ring road through Christ Church Meadow, one of the earliest schemes to raise the question of conservation priorities over motor convenience in urban areas. The road was not built, and Olive was temporarily expelled from the Labour group in 1959.

Olive and Edmund were also instrumental in the demolition of the infamous Cutteslowe Walls, which had been built in 1934 by a developer to separate private residents on his North Oxford housing estate from adjacent slum-clearance council tenants. For years these walls, which cut across the through roads and were seven feet high, topped by rotating iron spikes, had been the cause of great controversy and resentment.

On 9 March 1959 Olive, wearing a fur coat, watched as Edmund climbed up to a specially-erected platform and swung a hammer to ceremonially strike the first blow to knock down the walls. Edmund later recalled that in fact he missed, and almost toppled off the platform.

In the late 1960s, Olive successfully prevented most of Jericho from being demolished for slum clearance, having witnessed the destruction of her own beloved parish of St Thomas’s and neighbouring St Ebbe’s a decade or so earlier.

Olive was Lord Mayor of Oxford in 1974-5 and again in 1982-3, and in 1985-6 was Lady Mayoress, supporting her friend Roger Dudman, a widower. She sat on the Oxfordshire County Council for twelve years and became its first female chair, and its first Labour chair, in 1984.

Olive believed in educational opportunities for people of all talents and abilities and was an energetic chair of the College of Further Education (now the City of Oxford College). She was a governor of Oxford Polytechnic (now Oxford Brookes), receiving the first honorary degree awarded there and having the Humanities and Social Sciences building named after her.

She was made a Deputy Lieutenant of Oxfordshire and for her outstanding service to the city she was made an Honorary Freeman. She was also given the freedom of the City of London. Gibbs Crescent, a new street of social housing near Osney Marina, was named after her and opened by her in 1985.

On the national stage

Though for family reasons she declined to stand for parliament, Olive Gibbs played a part in national politics, and in particular in the campaign against nuclear weapons. In August 1945 she had been at an RAF dance in Boars Hill when news of the Hiroshima bombings broke. She later recalled:

The entire mess rose to its feet, throwing caps in the air and wildly cheering. I alone remained slumped in my seat, pale and trembling … I knew for a certainty that the worst crime in the history of man had just been committed.

In 1957 she was “upset by Nye Bevan, horribly upset” when he changed his position on the nuclear bomb. She became one of the founders of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in 1958 and came to national attention in 1959 when she attacked a pamphlet published by the Women’s Voluntary Service which described radiation sickness as “a nasty kind of tummy ache”.

Olive was a very active national chair of CND from 1964 to 1967. She disapproved of direct action and, when students painted CND graffiti on college walls, she personally scrubbed it out. Her period in the chair coincided with the start of Wilson’s Labour government; its failure to respond adequately to the demands of CND was a disappointment but not a surprise. On reflection, she concluded: “After 1961, it was impossible to be committed both to the Labour Party and to CND and yet many of us attempted to do just that”. She joined protest marches at Aldermaston with her close friend the left-wing Labour politician Michael Foot, and said of him. “We shared just about everything, except a sleeping bag.”

Despite this wider involvement, Olive Gibbs’s firm loyalty was to Oxford; she astutely understood the complex class and status issues of this university and manufacturing city. She remained fiercely devoted to St Thomas’s, the parish of her birth. In 1975, as one of her first acts as Lord Mayor, she hosted a reunion of former residents at the Town Hall – six hundred people attended.

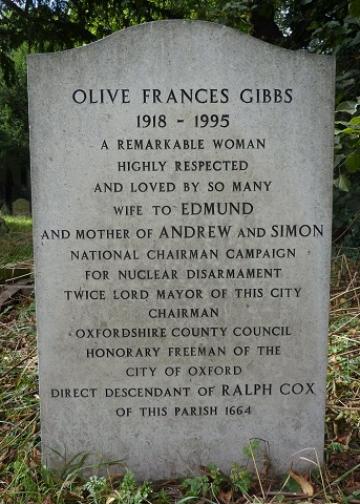

In 1989 she published her autobiography up to the 1950s, Our Olive, a lively and candid account. A heavy smoker from her forties onwards, Olive suffered from cancer and died of carcinoma of the lung in September 1995 at 95 Iffley Road, the Gibbs’s family home for over 40 years. She was 77. She was buried in St Thomas’s churchyard.

Those who knew Olive remember her as physically small – under 5 feet tall – but highly energetic and dynamic, a ‘firebrand’ with sparkling eyes and a raucous sense of humour. She was direct, and quickly let you know whether or not she approved of your views. Most importantly she was courageous and a woman of principle, who never let party politics stand in the way of what she knew to be right.

Liz Woolley is an Oxfordshire local historian.

This blog originally appeared on Women in Oxford's History.

Liz Woolley

Olive Gibbs’ headstone in St. Thomas’s churchyard. Photo credit to Liz Woolley.