Philosophical Reading and the Ascetic Ideal- Nietzsche: Genealogy, Analogy, Logic

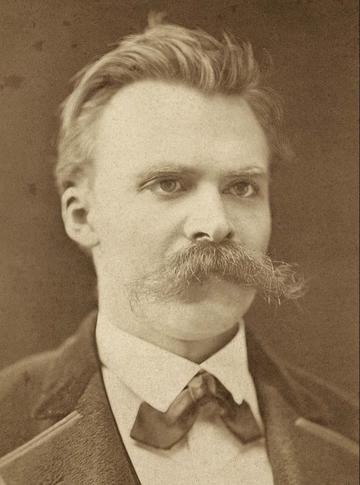

The Ascetic Ideal’ is the term Nietzsche uses in The Genealogy of Morality for the various ways in which the value-system of slave morality evolves, ramifies and spreads out into the broader reaches of Judaeo-Christian Western culture; and the concept that appears to play the decisive role in facilitating that mutation is ‘truthfulness’ (hence ‘truth’). One way of seeing this is to acknowledge the pivotal significance within the newly-established Christian form of life of the sacrament of confession: for it is in this context that the masochistic dimension of slave-morality’s denial of life comes clearly into focus. Christianity requires not only criticism of others who indulge in (what it has re-defined as) evil deeds, but the most rigorous form of self-criticism: I must ensure not only that I avoid evil deeds, but that I avoid evil thoughts (since, as Christ put it, indulging in adulterous thoughts amounts to committing adultery in one’s heart). Scrupulous self-examination is thus required, and any trace of evil detected must be declared – to the priest, and so to God; and the resulting humiliation thereby acquires both an instrumental and an intrinsic value (at once helping to bring us closer to God, and declaring our full awareness of our infinite distance from Him). Confession thus attempts to extirpate all manifestations of genuine vitality from our inner life, and in such a way as to confirm our own abasement; it both exploits and extends the self’s inevitable turning in on itself (as a condition of inhabiting a community), further excavating and enriching the radical idea that human animals contain such an inner life (one with its own relative autonomy, capable either of being expressed or being suppressed), but primarily with an eye to its potential for self-denigration.

Truthfulness thereby becomes a core Christian value, understood as essential to establishing an appropriate relationship to God incarnate (who describes himself as ‘The Way, the Truth and the Life’). We might call this a vision of flourishing human life as truth-seeking; on Nietzsche’s understanding of concepts as having an essentially genealogical identity, once such a vision is articulated and embodied, it becomes capable of relatively autonomous development – by which I mean not only that it is capable of finding new contexts which invite its application, but also that its nature is capable of being decisively modified by those contexts. Nietzsche is particularly interested in three such projections or extensions of this Christian valuation of truth: the first concerns its secular moral modalities (in which, despite dispensing with an explicitly theological frame of reference, honesty and truthfulness remain central virtues), but the other two concern modes of cultural activity that appear to be essentially unrelated to evaluative matters – the realms of science and philosophy.

Modern science quickly develops a conception of the life of the scientist as requiring dedication and self-sacrifice, even to the point of martyrdom for the sake of the truth (Galileo being exemplary here); but the account it delivers of reality begins by dismissing the deliverances of the senses as inherently illusory (as in accounts of secondary qualities as purely subjective phenomena), and then elaborates theories of the truth about matter as lying essentially beyond our unaided bodily grasp, and indeed as graspable at all only by means of mathematics – hence by pure reason and its access to essentially unchanging relations between numbers. Modern science thereby unfolds a picture of the truth that articulates it in terms of Being rather than Becoming - as if the truth about the empirical can only be captured in terms which transcend the blooming, buzzing incarnate encounter with other bodies (whether inanimate or animate).

Philosophy has, on Nietzsche’s view, been committed to valuing Being over Becoming from its origin; and its modern incarnations display a similar commitment, even if in significantly modified terms. Take Kant as an example: his Copernican revolution is intended to validate our assumption that we can attain genuine knowledge of objects in the empirical realm, but in order to do so he has to introduce a distinction between objects as they present themselves to us in experience and objects as they are in themselves, thereby inviting us to consider the latter as the locus of truth properly speaking. But the noumenal realm is by definition beyond the range of possible human cognition; hence, the way things really are with objects and with ourselves is placed essentially beyond our understanding, and within the grasp of reason only insofar as reason affirms both the fundamentality of its own categories (understood as essentially transcendent of the empirical) and their own essential inadequacy to the transcendental realm. This is how Reason’s punitive critique of itself imposes on us the humility needed to acknowledge the incomprehensible truth of the world, and of ourselves within it.

On such a reading, Kant’s revolution is an exemplary expression of the ascetic ideal in philosophy, hence a counter-example to the natural assumption that such enterprises as philosophy can be thought of as essentially non-evaluative (except insofar as they take value as their subject-matter), hence as not appropriately subject to evaluative judgements of this, or any other kind. And one familiar attempt to invalidate such a reading is to level the charge of the genetic fallacy: for insofar as Nietzsche’s critique of modern philosophy depends upon displaying it as a genealogical descendent of slave morality, it appears to conflate the question of its historical origin with that of its intellectual validity. Even if modern cognitive projects such as natural science and philosophy did emerge from a cultural matrix that was shaped by Christian value-systems, that can surely have no bearing on the intrinsic truth-value of either discipline, whether we focus on their methods or on the results they obtain by applying them.

The problem with this response, from Nietzsche’s point of view, is that the charge presupposes that a clear distinction can be drawn between the logic of a concept and its history; and that presupposition is not only one that his genealogical method contests, but is itself another manifestation of ascetic thinking. This is because it amounts to one more way of privileging Being over Becoming: the logic of a concept is defined in such a way as to insulate it altogether from the vicissitudes of history, and more generally of the realm of the cultural, the empirical, the contingent, which is set aside as irrelevant to the essential nature of concepts. Nietzsche’s contrary position is not well understood as simply inverting the evaluative poles of such an ascetic vision of concepts; it is not his view that the logic of a concept should rather be set aside in favour of, or even entirely dissolved into, the sheer contingency of history – for such a project would equally presuppose the sharp distinction between logic and history that he is attempting to put in question. His alternative genealogical model suggests rather that the relationship between the logic and the history in the constitution of the identity of a concept is internal, in the way that the identity of a family is constituted by the open-ended interaction of natural history and culture. A family tree reveals the identity of a family as established by the interplay of biology and society: under the incest taboo, the natural offspring of one set of parents marries the natural offspring of another such set, with their offspring amounting to a culturally-facilitated and -legitimized combination of both, who will then themselves look outside their own families for partners with whom to reiterate this grafting process. Such grafting does not deprive a family of its distinct identity; it is the means by which that identity is maintained through the vicissitudes of human natural history.

Reading the biological as the logical, and the cultural as the historical, the moral of Nietzsche’s entitling of his method is that the logic and the history of a concept are each essentially informed by the other: the logical structure of a concept at a given time makes it capable of accepting and absorbing a finite range of contextual factors, and whichever such factor takes that opportunity will reshape the concept’s logic in such a way as to reshape which future contexts will invite its application and which aspects of those contexts might then further reshape its logic, and so unendingly on. So when Nietzsche declares that ‘only a concept without a history can be defined’, he means to invoke an ascetic ideal of definition – the kind encapsulated in the Fregean ideal of a merkmal definition (in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions), the kind that might be appropriate in the atemporal realms of the mathematical, but which when applied to pretty much any other kind of concept simply distorts the phenomena under consideration, and does so in a manner which merits evaluative diagnosis and criticism. A genealogical perspective is thus not a means of depriving a concept of its identity, but rather the only appropriate way of disclosing it.

One of the key implications of such a vision of conceptual identity is the pressure it places on our assumptions about disciplinary identity and so more broadly on our understanding of what makes the various dimensions or branches of a culture both distinct and yet parts of a single form of life. For if a certain philosophical (and non-philosophical) view of logic and identity turns out to be appropriately criticized as an outgrowth of the ascetic ideal, it follows that philosophy is subject to ethical evaluation; and if the same is true of certain formations of natural science and art and history and philology, then a certain Enlightenment conception of what it is for a culture to be what it is will come under significant pressure.

Kant is once again exemplary here: for just as autonomy was the pivotal value in his vision of morality and politics, so it drives his presupposition that the only way to understand the nature of morality, politics, religion, art and natural science is by identifying the distinctive logic that gives each domain its identity and sharply distinguishing that logic from the others. This is why our capacity for empirical knowledge is given its own Critique, with morality and art each having its own Critical account, and equally separate accounts being provided of politics and religion. Throughout Kant’s critical project, a guiding principle is to avoid conflating domains with distinct underlying logics – conflating morality with politics, or with religion, or with empirical scientific knowledge; and the business of identifying and distinguishing these logics belongs to yet another domain which must be kept sharply distinct from all of those it surveys, and which underlies them all – metaphysics, or philosophy.

In this respect, Kant’s intellectual labours both reflect and empower a range of Enlightenment cultural forces that conceive of human progress as a matter of overcoming the illicit dominance of one cultural sphere over any others: the Church’s claim to dominance over all areas of human life is the canonical Enlightenment target here, but the progressive realization that politics should not interfere with matters of morality, or that artists should not feel beholden either to priest or politician, or that philosophy should cede to science the knowledge of nature – all are part of incarnating the principle of autonomy at the level of modern culture. Whereas on Nietzsche’s view, insofar as all the relevant concepts in each such domain are embedded in their historical and cultural contexts, then their distinctive identity is worked out in the genealogical interaction of each with the evolving response to contingencies exhibited in all. The result is that sharply distinguishing each domain amounts to a further expression of the ascetic ideal; and so developing accounts of each domain in which it is capable both of subjecting any others to fruitful critical engagement and of being subject to the critical engagement of others, and in which broader patterns of similarity and difference are rendered both salient and potentially explanatory, amounts to contesting the ascetic ideal in and through philosophy.

Nietzsche’s genealogical method has its own genealogy in earlier phases of his own writing, going right back to his first book, The Birth of Tragedy . This attempt to account for the nature and significance of Ancient Greek tragic drama does so in important part by recounting its history – the process by which its constituent elements and conception came into being within Greek culture, the causes of its all-too-hasty demise, and the unfolding of its consequences to the point at which the Wagnerian promise of its resurrection can dimly be discerned. More importantly, however, early versions of the two central affirmations of the Genealogy can also be discerned.

First, although the discussion ranges over a variety of issues in aesthetics (the nature of Greek tragic drama and so of Wagnerian opera, but also a taxonomy of different media and genres of art, and of aesthetic experience more generally), it also offers a metaphysical vision, a diagnosis of the basic structure of the religious response in human beings, and a transformative critique of philosophy as an intellectual enterprise; but what organizes this vast and potentially chaotic agenda of issues is one conceptual tool – the opposed figures of Apollo and Dionysus. That opposition structures Nietzsche’s account of each dimension of the aesthetic realm, but it is equally determinative in his vision of religion, metaphysics and philosophy; and yet, in each such analytic context, what is involved in a phenomenon being counted as ‘Apollinian’ or ‘Dionysian’ is importantly different, although patently related. What makes sculpture Apollinian and music Dionysian is not, for example, exactly what makes the Kantian narrative of concepts synthesizing the manifold of intuition interpretable as a marriage between Apollinian and Dionysian aspects of the human mode of sense-making, but neither is it essentially unrelated to the terms of that reading.

We might say: Nietzsche’s use of the terms ‘Apollo’ and ‘Dionysus’ is neither univocal nor equivocal, but analogical. The terms do not have one and the same meaning regardless of context, but neither do they have an essentially distinct meaning in each context (as when we talk of ‘banks’ in the context of rivers, and in that of financial practices). Rather, the meanings of those terms modulate in intelligible ways from context to context, thereby bringing out the internal relatedness of the phenomena within each context and so of the contexts themselves; Nietzsche’s coining and deploying of them in this way exploits a specific dimension of what one might call the projectiveness of words and their meanings – their inherent openness to new contexts, and more specifically their capacity to adapt to those contexts as much as the contexts prove adaptive to their presence. This is a vision of semantic identity as a discontinuous continuity or a continuous discontinuity – a process of self-overcoming through which each word discovers further reaches of its own capacity to disclose the world, which requires from their users the willingness to engage in what Aristotle would call right judgement from case to case (although he would limit this to the realm of ethics), and what Kant would call reflective judgement (although he would limit this to the realm of art).

The second key feature of The Birth of Tragedy is already implicit in those last comparisons. For a central concern of Nietzsche’s account of Ancient Greek tragic drama is that it flourished within a form of cultural life which refused to acknowledge what Enlightenment thinkers might call the autonomy of its various branches or domains. These tragic dramas were performed as part of a festival of religious thanksgiving celebrating the continued existence of the polis, and so could no more plausibly be characterized as aesthetic phenomena than they could be called purely political or religious; and their dialogue could be cited as authoritative for ethical debates, as well as many other kinds of dialogue (the very fact that led Plato to opposed to them the full resources of his fledgling new discipline, philosophy). This is one of the reasons why Wagnerian opera, built as it was around the idea of the ‘total work of art’ amounted to a rebirth of tragic drama: for it too aspired to overcome the Enlightenment dismemberment of culture, and so was committed to subjecting those dismembering forces (pre-eminent among them the contemporary descendents of Socrates) to a transfigurative self-overcoming from the perspective of art, as Nietzsche aspired to do from the perspective of philosophy.

More could no doubt be said about the specific differences between Nietzsche’s early analogical modes of reading and his later genealogical modes; one might also consider in more detail whether it would be more illuminating to think of the former as a species of genealogical reading, or the latter as a species of analogical reading. Either way, however, the two texts appear to be analogically related to one another, which suggests that it might be worth considering whether the individual texts that go to make up Nietzsche’s body of work attain their distinctive identity by virtue of the way each constitutes a new context within which the concepts pivotal to earlier texts find a new habitation and thereby a significant reformulation. In the present context, however, the point I wish to emphasize is that if Nietzsche – early and late – is someone who reads the phenomena which interest him analogically, then Nietzsche’s texts not only invite but demand that they be read analogically; unless we appreciate that the oppositions between Apollo and Dionysus and between master morality and slave morality are used analogically in their respective texts, then we will simply have failed to read them.

This paper was given by Professor Stephen Mulhall during the ‘Crisis, extremes and Apocalypse’ research network’s inaugural seminar on 14 November 2016.

A version of the material in the remainder of this paper originally appeared under the title ‘A Nice Arrangement of Epigrams: Stanley Cavell on Soren Kierkegaard’, in Gjesdal (ed), Debates in Nineteenth Century European Philosophy: Essential Readings and Contemporary Responses (Routledge: London, 2015).

Stephen Mulhall is a Professor and Fellow in Philosophy, and has been at New College since 1998. He was previously at All Souls College, Oxford, and at the University of Essex. Professor Mulhall’s two main areas of research are the philosophy of Wittgenstein, and some of the key figures in the Franco-German traditions of philosophy arising from Kant.