Quarantine used to be a normal part of life – and wasn’t much liked then, either

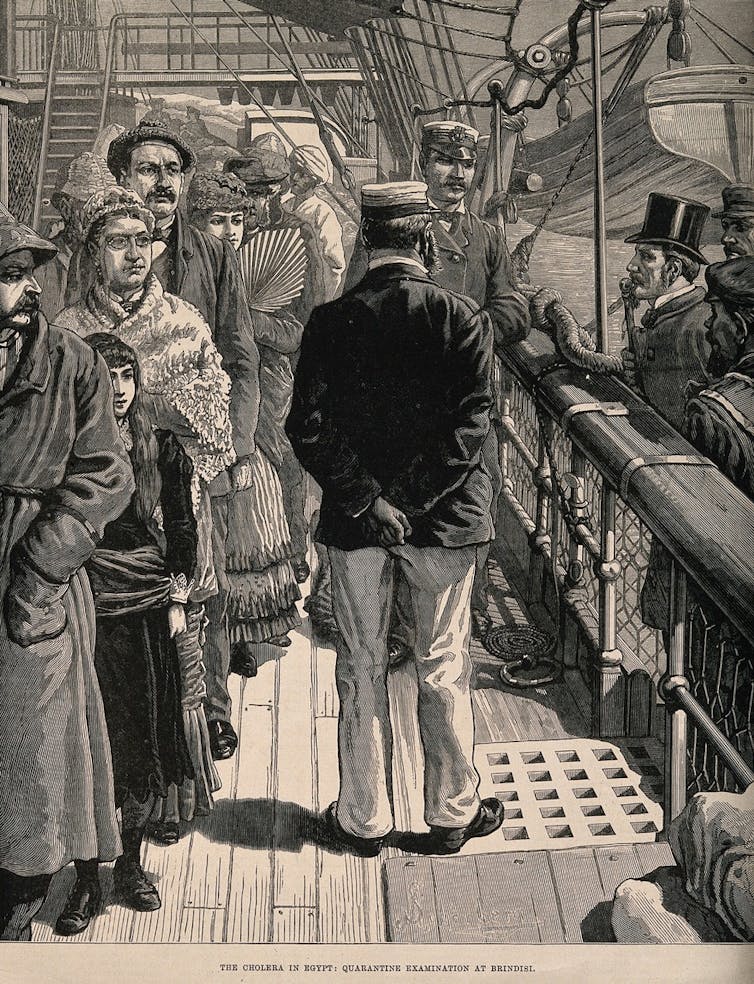

Lockdown, which one-third of the world is currently experiencing, is nothing new. Lockdown is a form of quarantine, a practise used to try to stem the spread of disease for hundreds of years by controlling humans. They were particularly common in ports in the age of commerce and empire: when humans gathered and traded in new environments, diseases often flourished.

Quarantine stations therefore quickly became a permanent feature of ports, although they differed in duration and practice – in a ship, a quarantine station, or the isolation of a whole neighbourhood. All new arrivals were isolated no matter whether there were rumours of diseases or not – a necessary evil, as no one knew when the next epidemic would strike.

But these measures failed to prevent the outbreak of immensely deadly epidemics because until the late 19th century there was little understanding of how different diseases spread. Such enforced detention of individuals and the sweeping powers allocated to governments made many people uneasy: in times of health and prosperity, quarantines were increasingly seen as an excuse for state intervention, and condemned as “instruments of despotism”.

‘Incalculable injury to the trade’

This critique was particularly acute among merchants, who framed quarantines as conservative institutions impeding a growing international trade - itself bolstered by the steam revolution, industrialisation, and colonial ventures.

The shores of the Black Sea, for example, were known as a hotbed for epidemics, being regularly assailed by outbreaks of the plague and cholera. Yet, in 1837, reflecting on the numerous epidemics that had claimed up to a tenth of the population, the British consul to Odessa nonetheless noted: “The real and ostensible evil has been the necessity for restraints to intercourse and business.”

Local quarantine laws were eventually reduced and even temporarily revoked after the Crimean War. Yet these changes had more to do with Russia’s modernising economy than with health policies. For this reason, quarantine was regularly restored as a means for protectionism and bargain, much to the dismay of Odessa’s traders: “The [re]establishment of the quarantine in the Ports of Southern Russia has more a political than a sanitary goal.”

As medicine and sanitation improved, many countries viewed quarantines like remnants of conservative commercial practices. Technological advancement, such as the development of telegraph lines, also generalised the idea that news from incoming epidemics could be received earlier, and better averted and monitored through prediction rather than prevention.

As the pace of trade and communications increased, the prospect of prolonged isolation and delay seemed too heavy a cost to pay, despite the risk of outbreaks. “Some are complaining of the rigours of this policy and the strains the quarantine imposes upon trade; others, mostly preoccupied with this dreadful pestilence (…) demand its continuation,” wrote a New Orleans newspaper in 1857, on the brink of an epidemic that would claim almost 5,000 lives.

Things haven’t changed much: the delayed responses of the UK and US to curb the epidemic were also dictated by a business-focused strategy. Now, as in the past, the balance between wealth and health is central to the debates surrounding quarantine measures.

Pathologies of solitude

The critics of quarantines did not just worry about the economy: some were political reformers who focused rather on the social costs and distress created by these measures.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the state’s responsibility to pay for workers’ wages in times of forced isolation. In the 1800s there was no conception of a welfare state, and in times of crisis most of the relief came from religious groups and philanthropic fundraising. But the concerns expressed then about the lasting social effects of the epidemic are relevant to this day.

Appalled by the ravages of cholera, a Russian priest worried in 1829 whether “once the outbreak is over and the freedom to go to the fields retrieved, the thrifty donations made until now would cease, thus ever again increasing distress”. Although the vocabulary has dated, the idea is familiar: the epidemic did not only make the poor poorer – the inadequacy in scope and duration of relief aid and policies created a deeper social crisis in the long run.

In 2020 as in the past, the possibility to self-isolate and to protect ourselves from contagious diseases is still determined by our economic conditions and the possibility (or not) of working remotely. At the same time, prolonged isolation can also contribute to create more difficult circumstances – economically, physically, and psychologically.

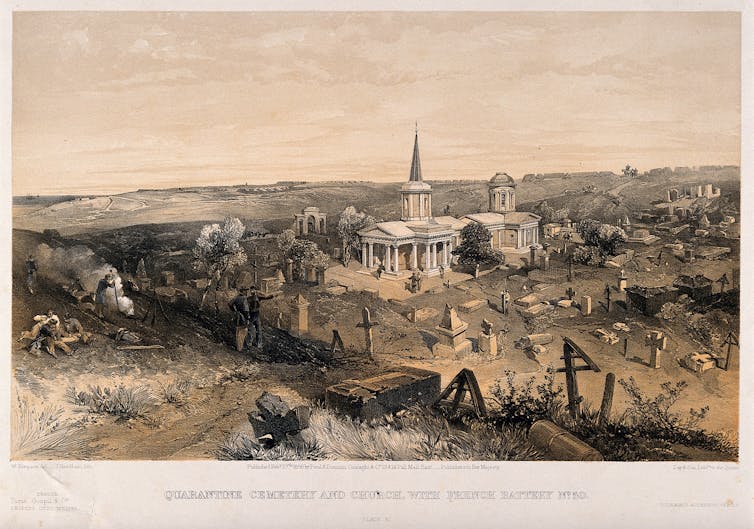

Quarantines were denounced in the 19th century as spaces that worsened the socioeconomic health. Some anti-contagionists even believed that, when it came to epidemics, the insalubrious and dangerous buildings of the quarantine stations were actually the root of diseases. Rather than being imported, they argued that epidemics were born in such stations due to the lack of air, light and hygiene. In 1855, during an episode of yellow fever in Louisiana, an article argued:

And to what use are these absurd quarantines, if not to create one more fear and to aggravate the consequences of the disease, by lowering from the outset the morale of the populations.

A sampling device

Quarantines sometimes succeeded, and sometimes failed at keeping mortality at bay. Yet lockdowns today, just like quarantines in the past, create situations that further endanger already physically and economically vulnerable groups.

Beyond the danger created by isolation, then as now, rumours of diseases are constantly manipulated. Social violence accompanied epidemic outbreaks, scapegoating communities but also targeting the presumed ill. This manifested in New York in 1858, when an angry mob of Staten Islanders, “disguised and armed, attacked the [quarantine] hospital from two sides, removed the patients, and set the buildings on fire” (as reported by Harper’s Weekly at the time).

Diseases were always seen as coming from an “outside” group or nation, and even today we must still redress attempts to qualify our current pandemic as a foreign disease. Quarantines act as a magnifying glass for social fractures, because they highlight who holds authority and power and who does not.

In the 21st century, quarantines are not the norm but the exception. But they have changed in scope, no longer circumscribed to single ships, buildings, ports or limited parts of the national territory. They have also led to cases of unprecedented power. Ultimately, because quarantines intervene in times of heightened human drama, they are about much more than disease prevention: then as now, they tell us stories of privilege, inequalities, and misfortune.

![]()

Olivia Durand, DPhil Candidate in Global and Imperial History, University of Oxford, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.