‘Return to Normality’ or Crisis as the New Normal?

If we were to adopt a macro-historical assessment of the effects of the post-2008 Crisis on Greek society, our first remark would have to be that the Crisis turned Greece into a society of low expectations. From the fall of the Military Dictatorship in 1974 to the eve of the Crisis in 2008, Greece had invested most of its collective efforts around four major national projects: “Democratization” and “Europeanization” in the 1970s; “social reconciliation” in the 1980s; and “modernization” in the 1990s and early 2000s. Underlying all four projects stood a common historical aspiration, namely the attainment of an historic leap from the semi-periphery of the world system to its modernized core.

Since the Crisis of 2008, however, Greece has been under the turmoil of successive social reactions: frustration, shock, indignation, shame, fear, resistance and, finally, resignation. For this reason, the Greek Crisis provides an excellent case study for the new field of the cultural history of emotions and affect theory, especially when compared to other societies which also experienced major crises in modern times. Unfortunately, though, the sequence of these alternating feelings has lately converged around the pathetic new national project of the so-called “Return to Normality”, otherwise known as Greece’s aspiration to “become a normal country.” This slogan has been embraced by both the former SYRIZA Government after the end of the Third Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in 2018 with front-page headlines in the party’s mouthpiece, Avgi, and by the ruling New Democracy (ND) party and its affiliated centre-right press. In 2015, the former leader of the centre-left PASOK party, Evangelos Venizelos, also proposed the same slogan as a basis for forming a national unity government.

The unfortunate relegation of Greece’s self-image today corresponds to a changed reality at the economic and social spheres. This shift essentially amounts to the fact that the Crisis has deformed the structures of the country’s economy, society and politics, yet without unleashing a new sociocultural and political dynamic capable of transforming them into a new, self-sustainable order. Practically, this means that the Greek economy, for example, might have left the bottom of the barrel of its long depression around 2017, but its structures remain warped and jammed in a state of stagnation caused by the gigantic Debt, a massive brain drain, the continuing bankruptcy of its banking system, high unemployment and the sadistic fiscal targets of the EU Troika. This catastrophic reality is openly acknowledged by non-Greek liberal commentators, such as Bloomberg News Agency, which recently remarked in one report that “Greece isn’t just starting from a low base like the Eastern Europeans – it’s doing so while dragging around a ball and a chain.” (Bloomberg, 8 January 2020).

Meanwhile, the official discourse of the Greek state, both under the SYRIZA and ND Governments, proclaims that Greece has exited the Crisis. After the end of the Third MoU in August 2018, the Tsipras Government claimed that, together with the supposed “exit from the MoUs”, Greece has also exited the Crisis itself, while ND, in a pedantic attempt to appropriate this curious “accolade”, claimed on the eve of the European Parliament elections in April of last year that the country will come out of its crisis “in the second half of 2019”. Today, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis claims that it was his Government that “pulled the country decisively out of the crisis”, while in 2018 he promised annual economic growth levels between 3 and 4 percent, which would indeed signal a return to recovery. However, for 2019, growth is expected to remain stuck at 1.8 percent, while the EU’s projection for 2020 [N.B. before the shocking downwardly revised figures following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic] was the same as last year, which means that Greece is set to remain in a state of economic stagnation for much longer.

A similar situation has been unfolding at the political level. The main effects of the Crisis on the Greek party system in the years 2011-19 were the fragmentation of the vote across many parties, high voter volatility between parties, and the rise of the far right. It is true that the elections of 7 July 2019 revealed some signs of stabilization. However, the return to a one-party government after eight years and the rise in the joint share of the vote for the two largest parties (ND and SYRIZA) from 64 to 71 percent, do not signal a return to a new two-party system. Voter volatility (the Pedersen Index) is still abnormally high, standing at 14 percent compared to 10 percent before the Crisis. The popular vote is still fragmented, especially in the wider centre-left, where parties like SYRIZA, KINAL and MeRA25 compete for the same anti-right-wing constituency. And the far right is again represented in Parliament, albeit through a party other than Golden Dawn.

From the foregoing it follows that Greece today might be experiencing Crisis in a milder form, but this should by no means imply that it has left it behind for good. One of the logical errors of the ideological model surrounding the deplorable notion of “Normality” is the hypothesis that between crisis and the exit from it there is always a clear dividing line. In reality, though, such neat models do not exist. What Greece has been experiencing since 2017 is a marginal transition toward a managed recession whereby elements of a putative “normality” are starting to enmesh with the continuing state of Crisis. For this reason, the ultimate danger for Greeks today would be to start getting accustomed to this hybrid condition, misreading it as a new state of “normality”. Clearly, this is what the Troika and its local supporters in Greece hope to achieve. If they succeed, the country’s real exit from Crisis will have to wait much longer.

* Excerpt from the paper presented at the conference Re-thinking Modern Greek Studies in the 21st Century, University of Oxford, 31 January 2020. Published in Greek in Ta Nea newspaper, 18 March 2020.

Alexander Kazamias is Senior Lecturer and Director for Politics at Coventry University. He is author of Greece and the Cold War: Diplomacy, Rivalry and Anti-Colonialism after the Civil Conflict. He has written many articles and book chapters on modern Greek history and politics, Greek-Turkish relations and the history and politics of Egypt. He has contributed press articles to The Guardian, Kathimerini, Ta Nea, EfSyn, Anti and Al-Ahram Weekly, and has given interviews to the BBC, ERT, Russia Today and several European newspapers.

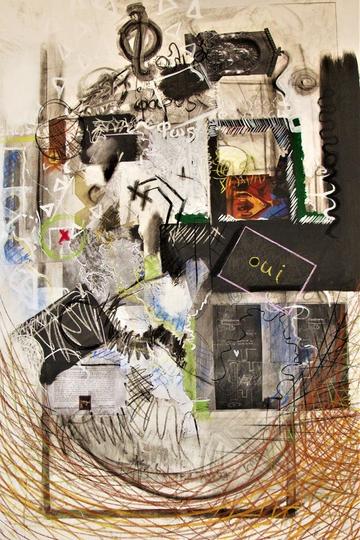

Ilias Toliadis, "In search of lost equilibrium through light" (2014). Acrylic, carbon & pencil with collage on canvas | 100cm x 160cm. Reproduced with kind permission of the artist.