Siren Voices

Sirens have slipped into speech - siren call, siren song, siren lure - as figures of temptation and threat. Our project explores how Western music interprets that combination of danger and attraction. Often, with patriarchal predictability, the combination is female. Using gender as a form of social policing, depicting women outside male sexual control as outside society has a long history in siren myth. The way that othering is done varies over time, but sirens have one constant attribute their powerful voice. This inspired us to work together with TransOxford, a local trans peer support group.

We wanted to explore what it would be like for othered voices to sing for themselves, since in music are either spoken as, spoken for, or spoken to, if they're verbal at all. We translated this into three project strands:

1) a podcast series;

2) a composition competition for Oxford secondary schools;

3) a digital album of siren songs, recorded by project participants.

Our podcast series interprets the power of the voice broadly, ranging from self-expression in Romantic Lieder to trans advocacy in the boardroom. We were astonished at people's willingness to donate their time and expertise, and special thanks go to two internationally renowned Classical musicians, soprano Anna Prohaska and pianist Graham Johnson, for their interviews. The whole series will be released together after recording an episode with the winner of composition prize, Erin Sharpe (Cheney School).

Erin's piece is remarkable because it eschews the tropes usually found in siren songs, populated by mesmerising but wordless monsters and wicked women. Instead, like sirens, the composition's self-penned lyrics are hybrid and ambiguous: lines like

and the rocks do quake for melodies of love and death

though they're much the same to you, and they're much the same to me.

could be sung either by sirens or the sailors they entrance.

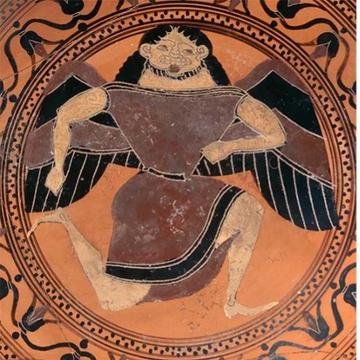

Both Erin's piece and the runner-up entry (by Zane Soonawalla, Magdalen College School) will feature in a concert later this year, highlighting repertoire we researched for the digital album. This includes (re)discovered pieces transcribed from Oxford manuscripts. Though recording was delayed by Covid-19 restrictions, we learned a huge amount about how much representations can shift while messaging does not. One of the things that surprised us is how thematically uniform compositions are across genres. In classical myth, sirens have a wide variety of associations, all linked to the persuasive power of the voice. Sirens who entrance sailors sailors coexist mythically with serene, celestial sirens who sing the music of the spheres and funerary sirens, who mediate between the living and the dead. They are not necessarily female-bodied: in archaic Greek art, sirens sometimes have beards and male pronouns, so that their hybrid ambiguity extends to gender.

A handful of English-language pieces (mostly settings of John Milton's Ode to a Solemn Musick) invoke celestial sirens, but most plump firmly for female-bodied temptresses, which blend water spirits from Greco-Roman and European folk traditions, such as mermaids, nymphs, or Rhine‑maidens. Culturally, this is interesting given the number of water spirits in different mythologies which aren't exclusively female-bodied – e.g. selkies – or, which, if female-bodied, like Mami Wata, can protect as well as destroy. Though these traditions weren't necessarily familiar to pre-modern composers, even Classically-inspired myth includes a far wider range of subject matter than the femme fatale trope. The traditions musical representations omit are therefore as informative as the ones they include.

The femme fatale trope, however, is not used solely to police gender: it also intersects with other power imbalances. One of the manuscript pieces housed in Oxford is Come Away, by the Jacobean court composer Alfonso Ferrabosco the Younger. This compares marine sirens to terrestrial ones, in this case black, unspecifically African nymphs who have come to King James' court because they want to be washed white. This early use of sirens to reinforce racial and colonial tropes is not unique, and underscores the main lesson we've learned through the project: the forms of othering may change, but its function stays the same. By investigating its role in music, we've hoped to show othering for what it is: not a description of a group, but denying them a voice.

This project has been generously funded by the AHRC-TORCH Graduate Fund.

Keeping in touch

The podcast, digital album, and concert details will be shared via TORCH and Twitter, @sirenvoicesox .

The project playlist is available here.

Organisers: Judith Valerie Engel – Hannah Massie & TransOxford – Winnie Smith

Human-bodied siren with wings and a beard, dressed in a tunic, on black-figure archaic Greek pottery.

Terracotta kylix: Siana cup (drinking cup) (detail), 575 B.C. Attributed to the C Painter. Greek (Attic), Archaic. Terracotta; black-figure, H. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm); diameter 9 5/8 in. (24.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1901 (01.8.6).