The Black Death, Medieval Mythbusting, and the London Charterhouse

Content warning: The text below includes a discussion of human remains.

Annabel Brodersen and Caroline Croasdaile completed a curatorial research micro-internship between the Oxford University Heritage Network and the London Charterhouse in December 2024. Their project explored the connections between the site and the Black Death in the fourteenth century.

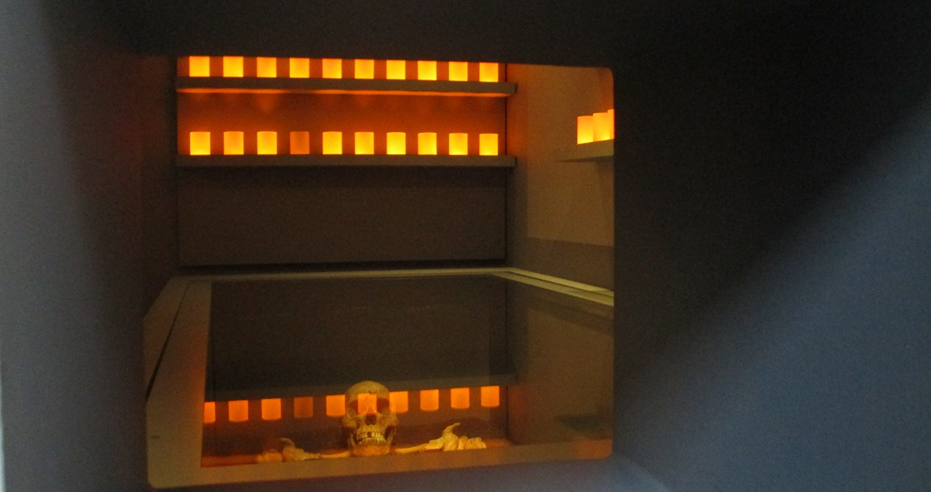

Peering into the re-constructed grave of a medieval plague victim at the on-site museum at the Charterhouse, an almshouse and living heritage site now in the heart of London, the flickering orange glow of candles surrounding the skeleton is both resonant and haunting. It reminds those who enter the museum that the victims of London’s first Black Death outbreak remain close. This is because in 1348 Charterhouse Square, today a peaceful green space marking the southern boundary between the London Borough of Islington and the City of London, was used as an emergency burial ground within the wider West Smithfield cemetery site. The reconstruction of the plague victim’s grave can be seen through opening a small door in the wall of the museum labelled ‘Ghosts’, which references the ghost stories written in the school magazine when the London Charterhouse was still a school for boys. We were able to visit the Charterhouse and Museum as part of a Curatorial Research Internship with the Oxford Heritage Network, and it was an inspiring start to what would be a fascinating week.

Our research project sought to answer the question of the presence of these ‘ghosts’, through researching whether there was an organised official response to the London outbreak of the Black Death in 1348. To answer our research question, we focused on two further questions: what details survive of the Charterhouse Square site as a plague pit in West Smithfield, and what evidence is there for an official response to the outbreak of the Black Death in 1348 in wider London and Britain?

The Charterhouse Square was established as an official emergency burial ground in 1348 by Sir Walter de Manny, who was linked to King Edward III, and it was located outside of the city walls as part of the West Smithfield cemetery site. The textual evidence for the number of plague victims buried at Charterhouse Square is ambiguous due to the conflicting numbers recorded by contemporary chroniclers and later historians. The Papal Bulls of 1351/1352 recorded over 60,000 victims, while John Stowe recorded over 100,000 plague victims in his ‘A Survey of London’ in 1598. However, the modern historian Barry Sloane argues that the chronicler Robert of Avesbury is the most reliable source, who writes that, ‘more than 200 bodies were carried to the cemetery for burial almost every day’, which is over 23,000 plague victims between February and April 1349.

The Crossrail excavations at the site in March 2013 shed further light on the estimated number of plague victims in West Smithfield. The excavation report estimates that there were over 5000 plague victims in West Smithfield, twenty-five of which were discovered at the Charterhouse Square site. Of the twelve individuals sampled for Ancient DNA (aDNA) testing, four were victims of the Black Death and were spread throughout the three phases of burial between 1348/9 and 1470.

Archaeological and textual evidence from the Charterhouse Square site emphasises that the burials were part of an organised official response to contain and prevent the spread of the Black Death in 1348. This evidence includes organised burial practices and the authorisation of the burial site by religious and monastic authorities. The Charterhouse Square site was not simply a plague pit for the haphazard mass disposal of bodies, but an official burial ground with individual, ordered graves that prevented the spread of the plague.

The West Smithfield Charterhouse site was not the only emergency graveyard founded in response to the 1348 arrival of the plague in London. In many ways a sister site to West Smithfield, East Smithfield was also created to cope with the staggering number of deaths Londoners were dealing with. The East Smithfield cemetery was founded ‘at the instigation of substantial men of the city’ and probably had ties to an initiative from King Edward III. It was located outside the city walls, next to the Tower of London, in what was then a semi-rural area. East Smithfield’s burials include mass grave trenches, a mass grave pit, as well as individual graves. It was excavated in 1986 and 1988, and 759 skeletons were recovered. Despite its emergency use in extraordinary times, the burials appear to have been organised and methodical. Even though the bodies were closely packed (sometimes five deep) they were carefully laid. Archaeologists believe that the total estimated number of burials for the site hovers around 2,400.

Like the Charterhouse, the East Smithfield’s site played host to a succession of different uses. In 1350 Edward III founded the Cistercian Abbey of St. Mary Graces there, which was later transformed into a Tudor manor house following the Dissolution. The site was then used to store and process food for the Royal Navy (1560-1785), before becoming the location of the Royal Mint (c.1811-1975). Royal Mint Court, now a Grade II listed complex of buildings, has housed Barclays Bank (1988-2000), and today holds a number of apartments and rental offices. It was recently sold to the People’s Republic of China who hope to transform it once more into an embassy.

The former employees of Barclays’s Bank reported eerie hauntings and odd noises late at night on what was once the site of East Smithfield’s plague cemetery. While ‘ghosts’ seem to plague the imagination of both the former schoolboys connected to the site and interns in the Charterhouse Museum, we’ve been assured by the Brothers, the current day inhabitants of the Charterhouse almshouse, that the only spirits present today are the ones in their cocktails!

Annabel is a second-year undergraduate student studying English Language and Literature, specialising in medieval literature. She is particularly interested in researching the intersections between early medieval art, archaeology and literature in living heritage sites like the Charterhouse.

Caroline is a final-year D.Phil. candidate in Archaeology. Her dissertation is entitled ‘Wearable Containers of Meaningful Things: English Late Medieval and Early Modern Jewellery to Enclose, Conceal, and Enshrine’. She participated in the excavation of the mass plague grave site of Thornton Abbey in North Lincolnshire.