Why I'm bringing poetry (back) into the NHS

March 21 is World Poetry Day – a day on which UNESCO celebrates poetry’s place in “our common humanity” and its “unique ability" to “capture the creative spirit of the human mind”. The day, like most global anniversaries, is an exercise in rebranding. “Poetry”, we learn, “will no longer be considered an outdated form of art”. Promising balladeers and haiku-masters will, we learn, get “fresh recognition”.

Fresh coffee might well be called for to deal with all this. Most of us have only just recovered from World Book Day on March 3, while those in the US, who have the whole of Eliot’s “cruellest month” set aside for things poetic, will have only a few days to regroup.

There’s a long tradition of anxious literary defences – from Philip Sidney’s An Apology for Poetry to Daisy Goodwin’s 101 Poems That Could Save Your Life. Somewhere in between, CP Snow’s 1959 lecture on the “Two Cultures” drew a line between “literature” and “science”, placing the former firmly on the back foot.

I’m aiming to blur that line a little. My Poetry of Medicine project, a discussion website and series of workshops, facilitates the reading of poetry, and reflection upon it, for doctors working in the NHS.

This may sound nefangled and wacky, but it’s far from trivial: the relationship between poetry and doctoring has a strong pedigree, and for a reason. Medical student John Keats might have left his apprenticeship early, but he carried on practising, after his own fashion. A poet, for Keats, was a “physician to all men”. And when not busy writing about plums in iceboxes, paediatrician and imagist poet William Carlos Williams was making house-calls and treating the children of New Jersey.

Doctors, both then and now, have been known to prescribe pages not pills – the vogue for “bibliotherapy” is nothing new. But physicians have, historically, also felt the need to heal themselves. Sir William Osler, whose work on what we now call the “bedside manner” broke new ground at the turn of the 20th century, insisted medical students should have “bed-side libraries”, read widely and nod off with the works of Shakespeare.

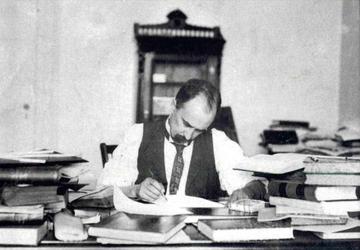

Nowadays, “Poems in the Waiting Room” – packs of small cards printed with poems – provide a welcome alternative to the usual battered copies of Woman’s Realm. The Hippocrates Prize celebrates poetry written by those in the NHS, and a new initiative in Scotland means that graduating medics receive a poetry anthology along with their degree. But doctors at our workshops report that current working conditions leave little time for creative thought. In the age of paper notes there was a chance for a marginal imaginative life. A Victorian doctor’s medical records (see below) is decorated both with quotes from Darwin and snatches of love poetry. Today, a typical GP faces not a patient and a page, but a screen of check boxes, guidelines and data requests.

MEASURING VALUE

So should we be worried about this increasing lack of creativity? Feedback from the workshops show that participants value having the space to reflect on their work in relation to literary texts. Elizabeth Bishop’s sonnets and T S Eliot’s monologues have opened up discussions about memory, burnout and the quest for happiness. But assessing the importance of the arts in any area is tricky. As the bioethicist Edmund Pellegrino notes, it is the humanities that “teach us to deal with the unmeasurable phenomena of human existence”.

Such emphasis on counting and measuring – from evidence-based research to targets met - has done little for the state of morale in the NHS today. The writer John Berger was anticipating a world hungry for numbers when he asked in his 1967 work about a country doctor:

What is the social value of a pain eased? What is the value of a life saved? How does the cure of a serious illness compare in value with one of the better poems of a minor poet? How does making a correct but difficult diagnosis compare with painting a great canvas?

THE LANGUAGE OF MEDICINE

Today’s doctors suggest it’s hard to answer these questions when the language used to judge their work seems ever more impoverished. As Iona Heath, former president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, described at a recent conference:

Unfamiliar words are beginning to permeate the health service and are heard in various combinations at almost every meeting: regulation, inspection, failure, enforcement, contract, competition, safety, risk, protocol, competency.

Meanwhile, she adds, “there is a set of words which seem to be slowly disappearing” – “words which include attentiveness, imagination, wonder, courage, difficulty, trust, commitment, touch, concern, conscience and tenderness”. There’s a kind of poetry to Heath’s speech, a way with words that comes from practising medicine as an art, as well as a science.

UNESCO’s claim for poetry is a universal one. Poetry works, they argue, by “revealing to us that individuals, everywhere in the world, share the same questions and feelings”. The sense of poetry’s value that has emerged in our workshops is a touch less strident but no less important. At its best, poetry’s complexity and linguistic play feels not for things that are “the same”, but those that are different, and critically so. It touches what is particular, complex, and hard to define.

In a world of big data, when healthcare is seemingly measured not by the act, but by the hour, this speak volumes.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Sophie Ratcliffe, Associate Professor in English, University of Oxford