Comics and Graphic Novels: The Politics of Form

We speak to Dominic Davies about the new network Comics and Graphic Novels: The Politics of Form and the complexities of bringing critical approaches to the comic form.

Have comics been overlooked in academia? Why do you think this might be?

Yes, comics definitely have been overlooked by many academics. This is in part because, by their very nature, they don’t fit easily into the disciplinary structures that we have today. Are they art? Of course, they certainly are, but because they’re usually collected together in strip or book form, circulated in newspapers or sold in bookshops, rather than hung in museums or galleries, it means they’ve often don’t get the attention of art historians and art theorists. Conversely, are they literature? Many comics look like books, and there are lots of self-labelled comics short stories and ‘graphic novels’. They have a beginning, a middle and an end, and most of them contain text that drives the narrative forward. But they are, also, fundamentally, groupings of sequential images as well as words. The field of literary studies might have the tools to deconstruct comics’ narrative dimensions, but how can literary academics presume to analyse their visual materials? This is one reason that, in its early incarnations at least, comics studies has mostly been located in media studies departments, sometimes even film studies departments.

However, probably the real reason for the slow uptake of comics by academia is that comics have traditionally been seen as a ‘low’ cultural form, one that is filled with coarse language, silly jokes and subversive sentiments and thus not worthy of critical attention. This is especially the case when they are contrasted with the notion of literature, say, as a ‘high’ cultural form with moral worth. This division still haunts comics, even as they have been embraced by academics in recent years, and causes much self-reflexive debate. It was only with the publications of longer comics such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Harvey Pekar’s American Splendour, or Joe Sacco’s Palestine, which move away from conventional superhero stories and tackle complex and serious issues (Spiegelman’s comic is about his father’s time in Auschwitz, for example) that academia started to take them seriously.

So these longer, more obviously ‘serious’ comics, have gained the form recognition in academic circles, and even today academics still tend to focus on them.

Are comics taught in schools and universities? If not, should they be?

Comics mostly aren’t taught in schools. In the U.S., throughout the latter half of the twentieth century when comics production really began to surge, comics were seen not as a medium to help children with their studies, but as distractions—and definitely not something to be studied. This prejudice lingers in education syllabuses today. But there are always exceptions—a comic about anti-apartheid activism is read in schools in Cape Town to educate students about South Africa’s history, for example. And we are seeing comics-only modules cropping up in higher education now. But this is in large part dependent on whether there is an academic in an English Literature department who happens to have an interest in comics, and the energy to build and offer these modules. One good example is Dr Paul Williams, who has set up a comics-only module at the University of Exeter, and who is coming to give a seminar at our TORCH Network.

As to whether or not comics should be taught in schools and universities, I think the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. The form is so rich, it does so many things that literature or art, as separate mediums, cannot. Indeed, in recent years, there’s been a surge in the kinds of stories that comics are being used to tell—there are now sub-genres within the field, such as autobiographics (autobiographical comics) and comics journalism—and in the popularity of comics, as more and more people find stories they can relate to.

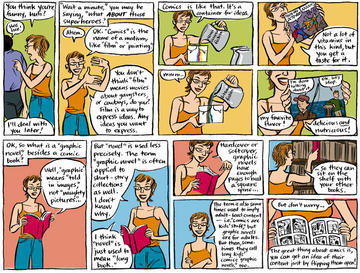

Is there a difference between ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’?

That depends on who you ask. As comics have been deemed worthy of academic attention, the term ‘graphic novel’ has become more widely used. This is definitely related to the issue of ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms of culture I mentioned above. The term ‘comics’ is still associated with short strips in newspapers, or superheroes, and these still aren’t really taken seriously. The term ‘graphic novel’ has come to be used by academics to refer to the longer form comic, usually published all in one go as a book – and that is somehow a ‘higher’ cultural form. It is the term ‘graphic novel’ that high street bookshops such as Waterstones and Blackwell’s use to categorise the comics they sell, and again I think this is related to the idea about what is ‘serious’ literature and worthy of being read by the kinds of people who frequent those stores. While the distinction between the terms ‘comic’ and ‘graphic novel’ has a certain usefulness, there’s a great deal of academic debate about its implicit politics. Graphic novels are still comics, and owe their existence to long histories and rich traditions that extend back into the twentieth century and earlier. Their relabelling as ‘graphic novels’ dismisses this history. Some critics even see the term as being cynically deployed just to make comics more palatable to middle class readerships, academics, and university English departments.

There are numerous other labels that can be used to describe the comics form. I prefer to use the term ‘long-form comics’ rather than ‘graphic novels’ when talking about book-length comics, because it means that we don’t forget the form’s long and valuable history. But it’s important to remember that even under the umbrella term ‘comics’ is a huge diversity of different kinds of reading experience, some of which bear little resemblance to one another.

Discussions around terminologies and definitions have always been at the centre of academic criticism on comics, and these debates are still ongoing, so there’s still no straightforward answer to this question. This Network will include seminars about ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’, but will remain self-aware and open to thinking about how these terms are used and what the implications of this usage might be.

Can you apply traditional critical theories to the comic form?

Comics can be analysed with the critical theories that art historians might use, or with other tools from the broader field of visual cultures, such as W.J.T. Mitchell’s work on ‘picture theory’. But since they’re also narratives, literary criticism’s numerous theories such as narratology and discourse, not to mention other fields such as feminist or postcolonial criticism, have a role to play here. Though comics haven’t had the attention that they deserve from academia, the relatively few critics who have written monographs on them and, in the occasional case, devoted their entire careers to them, have come up with some really sophisticated theories specifically designed for reading comics.

And comics are inherently interdisciplinary, so the tools needed to read them are also interdisciplinary. So it’s really important that our network creates a space for conversations to take place across the traditional disciplinary divides. We’re trying to bring literary critics into dialogue with visual cultures scholars. And given that the comics and graphic novels we’ll be discussing in the seminars cover such a range of topics, it’s also really important that we welcome historians, geographers, and politics students into the conversation as well. There are also comics being produced in a number of different languages, and so we have committee members from modern languages departments.

How can people get involved and what can we look forward to?

Because the history of comics criticism has always been practiced as much by artists themselves (Will Eisner, Scott McCloud) as it has by academics, we are going to alternate visiting academic speakers with visiting artists to learn more about how actual practitioners go about writing and drawing their comics. So in Michaelmas Term 2016, we have Dr Helen Iball from the University of Leeds talking about autobiographical comics, and Dr Charlotta Salmi from the University of Birmingham presenting some of her recent research on protest and graphic novels in the Middle East. But we also have some artists coming to present their work and offer their reflections, such as Karrie Fransman, who did a TEDx talk on comics quite recently, and Samir Harb, a geography PhD student at the University of Manchester who is also a published comics artist.

The seminar will run every two weeks throughout term time, and each of these speakers and artists will circulate some comics for participants to read in advance. It’s really important that the Network gets people to actually start reading some comics as well as simply talking and hearing about them.

In addition to the bi-weekly seminars we’ll also have one-off events, in collaboration with other TORCH Networks or other seminar groups based at the university. For example, Jennifer Howell, author of The Algerian War in French-Language Comics (2015), is coming to give a one-off seminar in November 2016.

All will be welcome to attend any of the seminars and talks we’ll be putting on, and we’ll be advertising each event through TORCH, the English Faculty, and various other mailing lists and outlets. In addition, we are currently building up a mailing list of our own, to which you can subscribe by emailing dominic.davies@ell.ox.ac.uk or comics@torch.ox.ac.uk. We’ll also be active on social media, so people will soon be able to like us on facebook and follow us on twitter, and we’ll feature regular blogposts about comics-related topics on the TORCH website as well.

Image: Courtesy of Jessica Abel, Wikimedia Commons

Oxford Comics Network, TORCH Networks