Excavating Public Collections: Uncovering the National Trust’s Ancient Greek Vases

Abigail Allan

As outlined by Dr Ollie Cox, formerly of the Oxford Heritage Partnerships Team, there is a gap between academic research and action in heritage settings.[i]Collaborative Doctoral Awards (CDAs), designed and completed in partnership between organisations and universities, can begin to close this gap. Abigail Allan's CDA with The National Trust aims to illuminate the Trust’s collections of ancient Greek vases. This CDA stemmed from a Curatorial Micro-Internship which you can read about here. The following blog reflects on Abigail's experience.

Greek vases are one of the least known categories of items in the NT. That the NT own such objects, however, is unsurprising: as caretakers of country houses designed and lived in by the elite, alongside their accompanying contents, the NT necessarily holds Greek vases, collected by the British elite since the late 1700s. Of key importance to this collecting was the phenomenon of the ‘Grand Tour’, described as a ‘finishing school’ to their Classical education.[ii] Here, acquiring antiquities to showcase that education was participants’ ‘most obsessive ambition’.[iii]

With over one million items in its collection, the NT cannot possibly know everything about everything – excitingly, there is plenty of scope for future research. Before this project began, the number of Greek vases in the NT was unknown. Previously, many had not been identified as Greek or dated as antiquities. This made them difficult to locate in simple catalogue searches. To identify the vases, keyword searches of both the NT’s online catalogue and internal Collections Management System were undertaken, using terms pertaining to vessel usage, misnomers, descriptive terms, and technical terms.

72 Greek vases across 11 properties in England and Wales, most of which are unpublished, have now been discovered. The vases found are from Corinth, Attica, South Italy, and Etruria, dating from c. 600-300 BC. The 11 properties are shown on fig. 1. In addition, Lyme Park has 38 Greek vases on loan from Manchester Museum, and Charlecote Park has two on loan from the family associated with the property.

Map of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland showing the NT properties containing ancient Greek vases. The greyed-out segments indicate loans from external organisations and individuals. © Abigail Allan

Now that the vases have been collated, the first part of this CDA concerns cataloguing them. Cataloguing, or re-cataloguing, is crucial in heritage settings because, as detailed by Spectrum and ICON (the Institute of Conservation), the museum management bodies defining the international standards used in collections care, ‘every museum has a responsibility to research the objects in its collection’ and record this research.[iv] By cataloguing the objects, I have developed a variety of skills specific to the study of Greek vases: I have been required to date the vases stylistically and identify iconography, painters, workshops, techniques, and shapes (including more unusual examples), and determine where the vases were made from the clay type and painting style. Additionally, I have developed vase handling and vase photography skills. I have also undertaken provenance and provenience research (provenience referring to the vases’ ancient history and provenance referring to its modern history).

The CDA’s second part concerns further research into the vases at three properties, uncovering their collections and display history: Nostell Priory, Charlecote Park, and Sudbury Hall. This is being undertaken to provide crucial information for the thesis’ third component: the curation of the vases. Perhaps not all academic research needs to be publicly shared, but for objects in public ownership like these vases, I believe it is vital. As a charity for public benefit, the NT’s purpose is not simply to preserve places and objects, but to make them accessible: its collections, as its slogan proclaims, are ‘for ever, for everyone’. Curating these vases is a key way details about them can be shared with the public in an enjoyable way.

This thesis will produce three different displays of Greek vases, each exhibition focusing on different aspects of Greek vases, chosen to suit each collection. At Nostell, the temporary exhibition will concern the vases’ modern history and their importance to their collector, Charles Winn, exploring both his emotional connection with them and his social need to collect items, including antiquities, to become an appropriate heir. People’s personalities are known to be represented through their objects,[v] and in the case of Winn, the vases reveal a less public facet of his personality. In environments with ‘an abundance of objects’,[vi] revealing the rich reasons they were collected can pique interest and clarify understanding, fulfilling the NT’s aim to ‘bring places to life’.

At Charlecote, the temporary exhibition will focus on the artistry of vase-painting, considering the iconography and painting techniques employed on these vases, the finest in the NT – one of the vases, a black-figure hydria (water jug) depicting three Amazons (warrior women) on horseback and dated to the late sixth century BC is pictured here (fig. 2, NT 532414). Importantly, this exhibition will fit with Charlecote’s upcoming programme of Heritage Crafts.

Fig. 2 Greek Vase in the National Trust Collection of Charlecote Park © Abigail Allan

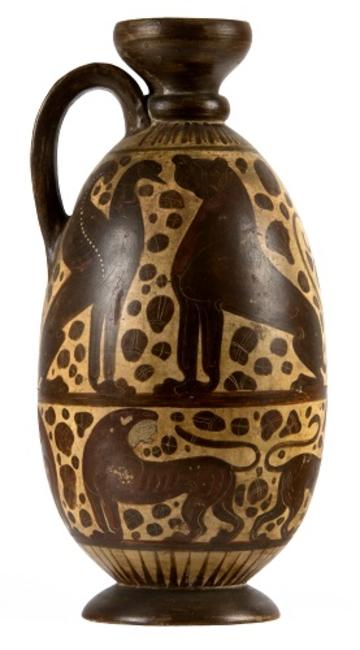

Finally, at Sudbury, the Children’s Country House, the permanent vase display will, of course, target children. The vases are currently displayed in a room whose overall theme is travel and adventure, presented alongside and between books about topics from all over the world. In the centre of the room is a large map-rug (showing one of the vases), paired with model ships, encouraging children to move the ships across the map just as goods moved across the world to Sudbury. In keeping with the theme of adventure, the interpretation of the vases will focus on the monsters depicted on them and the myths they inspired. Fig. 3 (NT 652471), dated to the mid-seventh century BC, shows one of the vases with monsters – it has a sphinx (a lion with the head of a woman) below a lion with the wings, neck, and head of a swan. As one of the most engaging facets of vase studies for children, this will be perfect for introducing children to the wonder and excitement of the ancient world.

Fig. 3 Greek Vase in the National Trust Collection of Sudbury Hall © Abigail Allan

This CDA will therefore position Classical academic scholarship at the interface with public humanities, reaching a wider audience than academics alone. It will provide an example of the impact museums have on public awareness of academic disciplines, by sharing the academic knowledge gained throughout directly with the public.

Abigail Allan is undertaking a Collaborative Doctoral Award (CDA) between the University of Oxford and the National Trust, supervised by Dr Thomas Mannack (Oxford) and Simon McCormack (National Trust). Her CDA intends to catalogue the National Trust’s collections of ancient Greek vases before researching and curating the vases at three properties: Nostell Priory, Sudbury Hall (the Children’s Country House), and Charlecote Park. Abigail is also the Assistant Curator for Lady Margaret Hall’s Art Collection and is a Curatorial & Museum Consultant for Fairfield House, Bath. She has previously worked for National Historic Ships UK, the Ashmolean Museum, and the British Museum.

Find out more about the National Trust Partnership here.

Find out more about the TORCH Heritage Programme here.

[i] Cox, Oliver. (2021). ‘Twenty-first-century Visitors in Eighteenth-century Spaces: Challenges and Opportunities,’ Hague, Stephen George and Lipsedge, Karen (eds.) At Home in the Eighteenth-century: Interrogating Domestic Space. London: Routledge. 307-324, pg. 307.

[ii] Coltman, Viccy. (1999). ‘Classicism in the English Library. Reading classical culture in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries’, Journal of the History of Collections 11(1): 35-50, pg. 42.

[iii] Haskell, Francis. (1996). ‘Preface,’ Wilton, A. and Bignamini, I.(eds.), Grand Tour: The lure of Italy in the eighteenth-century. London: Tate Gallery. 10-12, pg. 11.

[iv] Ambrose, Timothy and Paine, Crispin (2018). Museum Basics: The International Handbook. 4th Edition. Oxford: Routledge, pg. 208.

[v] Nostell Priory Collections Development Policy 2020, clause 2.

[vi] Cox, Oliver J. W. (2015). “The ‘Downton Boom’: Country Houses, Popular Culture and Curatorial Culture,” The Public Historian 37(2): 112-9, pg. 118.