The first printed and illustrated edition of Dante’s Comedy

The late summer of 1481 saw the publication, in Florence, of an extraordinary book: Commentary of Cristoforo Landino, Florentine, on the Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Florentine Poet. The Comedy at this date was no longer a novelty, having been completed by Dante shortly before his death in 1321. The first printed edition of the work had appeared in Foligno in 1472. Yet the inaugural Florentine printing was one of the most ambitious undertakings in the entire history of the printed book.

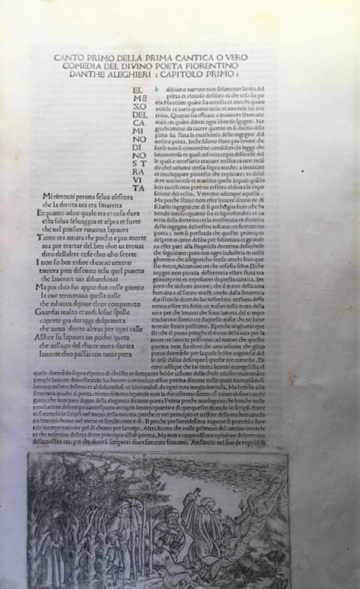

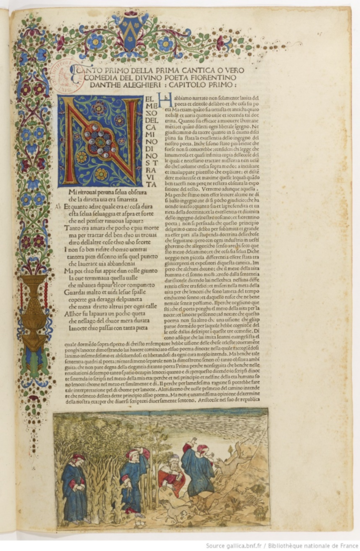

The driving force behind this new edition of the Comedy, Cristoforo Landino, was a humanist scholar who had recently established himself under the powerful patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici. As the title already announced, the book foregrounded the annotator even before the poem’s original author. Dante’s text had been commentated from the time of its creation, very much like holy scripture; yet Landino’s explanatory notes expanded on the page, almost to the point of swallowing up Dante’s verses altogether. In addition, the volume was planned to include illustrations throughout: one for every canto of the poem. (Fig.1) The text was set up in letterpress, but spaces were left for the line-engraved images (made by intaglio on metal plates) to be inserted, calling for two distinct printing processes. The printer, known in Tuscany as Nicolò di Lorenzo, who like other early practitioners of the craft in Italy came from north of the Alps, had already experimented with illustrations in a previous Florentine publication of 1477, Il Monte Sancto di Dio, which included three pictures. That experience may explain his recruitment to the far more ambitious Dante project.

1. The opening page of Commento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la commedia di Dante Alighieri poeta fiorentino (Florence: Nicolò di Lorenzo, 30 August, 1481). The first twenty-one lines of Inferno are framed by part of Landino’s comment on the first line of the poem. At the foot of the page is an engraving by Baccio Baldini (?) after Sandro Botticielli. Bodleian Library, Bodl. Auct. 2 Q 1.11.

The book had both a cultural and a political agenda. It attempted to establish a commonly agreed version of the text, and in the process to demonstrate Tuscan authority over both the work and its author. Dante had died, in political exile from his native Florence, in Ravenna: repeated attempts by the city of Florence (including a representation by Lorenzo de’ Medici himself) to claim the bones had been rejected. Meanwhile the spread of the Comedy throughout the Italian peninsula, witnessed by the survival of some 600 manuscripts, had led to verbal confusions and adaptations as the text was copied by scribes incompletely familiar with the Tuscan of the original. The lengthy preface by Cristoforo Landino announced Dante’s ‘return’ to Florence, and praised the Medici alongside the Signoria as leaders of the city and patrons of this prestigious cultural project.

I affirm only this, that I have liberated our citizen Dante from the barbarity of many foreign idioms in which he had been corrupted by many commentators, and thus so pure and simple it seemed to me my duty to present him to you, our illustrious lords, so that in the hands of that magistracy which is most high in the Florentine Republic, he should be restored to his homeland after long exile, and not recognized as romagnolo or lombardo nor any of the languages of those who have glossed him, but simple Florentine, a language which is greater than any other Italian idiom, as is shown clearly by the fact that no one ever expressed genius or doctrine nor wrote verses or prose, who did not attempt to use the Florentine idiom.

In his exposition of the poem, Landino drew heavily on earlier writers, but his particular contribution was an emphasis on spiritual allegory, which was encouraged by the Neoplatonic thought then current in the Medici household. His commentary was reprinted in subsequent editions of the Commedia well into the sixteenth century. Ironically, the text of the 1481 Commedia itself left much to be desired, mainly because of poor copy-editing. This is one indication of haste in the book’s production, although the particular circumstances are not yet fully understood.

A further sign of pressure on the publisher is the incomplete state of the illustrations. Only three, in fact, were ready in time for the first issue of the book. Of 156 surviving copies, the majority contain just the first two or three engravings relating to the initial canti of Inferno. Sometimes one of these is repeated; in the Bodleian Library copy, the repeated second image is printed upside-down. Some copies contain further images, up to a total of nineteen: these, separately printed, were tipped or glued into the book – either by the printer or possibly by private owners of the volume who acquired the pictures from the publisher to insert.

Another indication of the lofty ambition of this book project is the involvement of the young Sandro Botticelli. The artist – also operating at this time in the orbit of the Medici – undertook from around the same period to make a complete set of illustrations to every canto of the Commedia, to accompany a luxury copy of the manuscript probably intended for a Medici patron. These famous drawings, which remain incomplete, are now divided between the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin and the Biblioteca Vaticana in Rome. Giorgio Vasari mentions Botticelli’s interest in Dante as well-known, to the point that the artist was reproved for pretending to a knowledge of the Commedia beyond the capacity of a mere artist. It is not at all unlikely that Botticelli did, in fact, know the poem well (as did other Tuscan artists of the period, including Signorelli and Michelangelo), nor that he made more than one series of Dantesque images. The nature of Botticelli’s involvement in the 1481 printing of the Commedia remains, however, uncertain and intriguing. On somewhat shaky grounds, the preparation of the images for this publication has been attributed to the Florentine goldsmith and engraver Baccio Baldini. Vasari, writing in the mid-sixteenth century, described Baldini as an artist lacking in imagination, and claimed that ‘everything he did was based on inventions and drawings by Sandro Botticelli’. Little, however, is really known about Baldini, which makes it hard to ascribe works to him on stylistic grounds. What does appear, from the visual evidence of the pictures made for the printed book, is that the engraver – and perhaps, after all, it was Baccio Baldini – had access to a range of visual sources including older manuscripts of the Commedia and Dante-related designs by Botticelli.

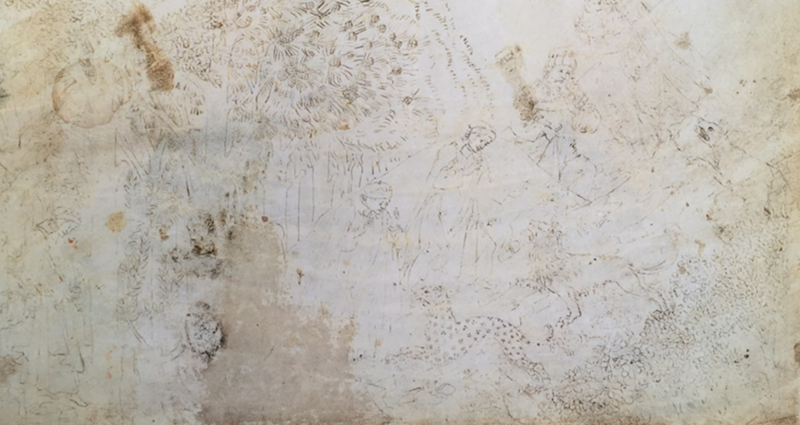

The first three plates of the printed edition of 1481 appear to have been based closely on designs by Botticelli. The respective images to accompany the first canto of Inferno are not identical (and the comparison is made difficult by the faded condition of the drawing), but they are sufficiently similar to lend support to this argument. (Figs. 2, 3 and details)

2. Sandro Botticelli, drawing for Inferno I: Dante, the Beasts, and Virgil (c.1480). Facsimile, 1887. Zeichnungen von Sandro Botticelli zu Dantes Goettlicher Komoedie: nach den Originalen im K. Kupferstichkabinett zu Berlin (Berlin: G. Grote’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1887). Taylor Institution Library: REP.X.55 (plates).

3. After Botticelli, engraving for Inferno I in Commento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la commedia di Dante Alighieri poeta fiorentino (Florence: Nicolò di Lorenzo, 1481). Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Réserve des livres rares, RES-YD-179. Source gallica/bnf.fr / BnF.

Dante in the dark wood. Details of the images above.

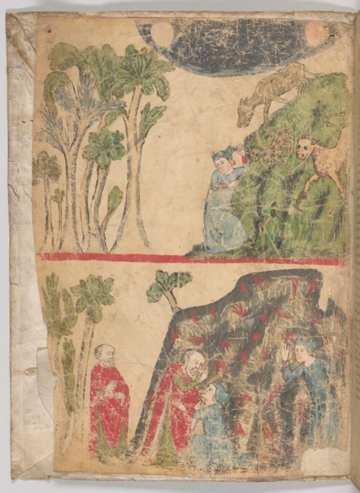

Certain details suggest that the artist collaborated closely with the commentator. The rendition of the dark wood by Botticelli, and so also by the engraver in this case, departs from previous representations, of which a mid-fourteenth-century Florentine example is typical. (Fig. 4)

4. Dante and the Beasts; Dante and Virgil. Illustration to Inferno I. Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, with anonymous commentary. Florence, 1345-55. Pierpoint Morgan Library, MS M.676. By permission of the Pierpoint Morgan Library (tbc).

The difference in Botticelli’s image is the far stronger emphasis on the wood as enclosing and entrapping the visionary figure of Dante. This resonates with Landino’s Neoplatonic excursus, in relation to this canto, on the mystical passage of the soul from the darkness of the material world to spiritual enlightenment.

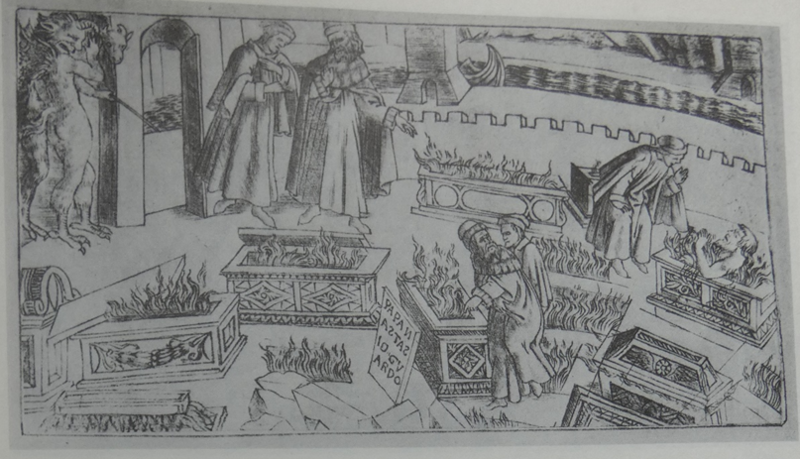

However, it would appear that Botticelli’s progress on the Dante drawings was interrupted (the painter is known to have travelled to Rome, probably in July 1481, to work in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, returning to Florence in the following spring), and the publisher went into print in August 1481 with no more than three completed illustrations. He subsequently commissioned sixteen more cuts, before abandoning the images, which cost money and were taking too long to prepare. For most of the new illustrations, the designer appears again to have had access to drawings by Botticelli – as can be seen from a comparison of the respective images of the open tombs of the heretics in the City of Dis. (Figs. 5, 6)

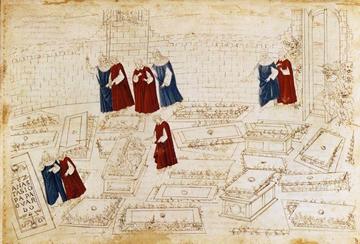

5. 5. Sandro Botticelli, Drawing for Inferno X: Dante and Virgil in the City of Dis. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, cod. Reg. lat. 1896, fol. 100r. Photo: Web Gallery of Art / Public domain.

6. 6. Baccio Baldini (?), Dante and Virgil in the City of Dis: Inferno X. British Museum, Dept of Prints and Drawings. Photo: A.M. Hind, Early Italian Engravings, pl.167.

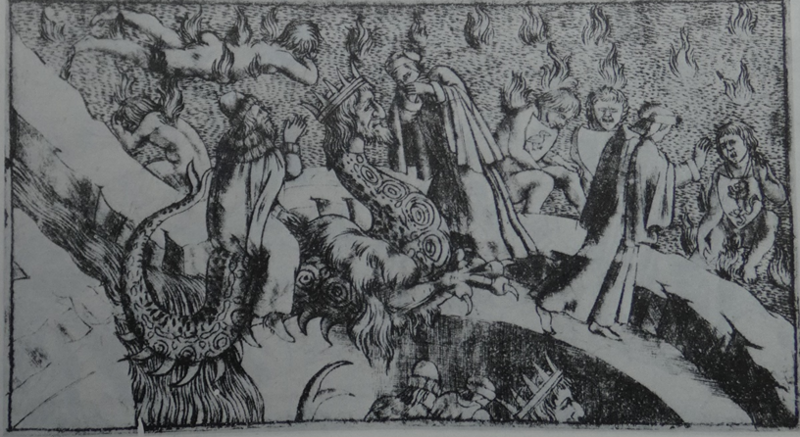

Similarly, a juxtaposition of Botticelli’s drawing of the monster Geryon with that in the engraved version shows the printer’s équipe working with material from the painter’s shop. (Figs. 7, 8)

7. Sandro Botticelli, drawing for Inferno XVII: The Desert of Burning Sands; Descent on the back of Geryon. Facsimile, 1887. Zeichnungen von Sandro Botticelli zu Dantes Goettlicher Komoedie: nach den Originalen im K. Kupferstichkabinett zu Berlin (Berlin: G. Grote’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1887). Taylor Institution Library: REP.X.55 (plates).

8. Baccio Baldini (?), The Desert of Burning Sands; Descent on the back of Geryon: Inferno XVII. British Museum, Dept of Prints and Drawings. Photo: A.M. Hind, Early Italian Engravings, pl.170.

Earlier manuscripts of the Comedy had brought together text, commentary and illustrations. In some ways the printed edition of 1481 was a summation of a century and a half of experimentation with the poem. The typeface used by Nicolò di Lorenzo was a conservative one, conforming to the script of fine manuscripts of the earlier part of the century. The fact that some of the printed images were coloured – this was usually done, to judge from known examples, by professionals – also indicates that the appeal was to an existing market for attractive illustrated editions. In an example now in Paris, colour has been applied to the engravings and in addition the opening initial letter has been elaborately decorated by what was certainly a professional hand. (Fig. 9)

9. Opening of Inferno I in Commento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la commedia di Dante Alighieri poeta fiorentino (Florence: Nicolò di Lorenzo, 1481). Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Réserve des livres rares, RES-YD-179. Source gallica/bnf.fr / BnF.

The price for a copy of this book without costly additional illumination and binding was not especially cheap, yet (as one early reference confirms) will have been – unlike an illuminated manuscript – within the reach of a relatively prosperous artisan. Landino himself claimed in 1484 that 1,200 copies of the work with his commentary had been sold; and a further six editions were issued before the end of the century. So, if in some ways the 1481 edition looked backwards, in others it anticipated a long and glorious future of editions of what after 1555 became known as the Divine Comedy, accompanied both by extensive commentary and by more-or-less elaborate illustrations.

In order to gain a better understanding of how this remarkable book was planned and assembled, an online symposium on 4 May 2021 will use new technology to compare a number of the surviving copies held by libraries in the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom. The event is organised by Dr Tabitha Tuckett, Rare-Books Librarian, University College London, Cristina Dondi, Professor of Early European Book Heritage, University of Oxford and Secretary of the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL), and Dr Alexandra Franklin, Co-ordinator, Centre for the Study of the Book, Bodleian Libraries. For information and to register for the (free) symposium, see:

Essential bibliography

A.M. Hind, Early Italian Engraving (New York and London, 1938), Part I, Florentine Engravings, vol. I, Catalogue, pp.99-116; vol. II, Plates, nos.162-71.

Peter Keller, ‘The engravings in the 1481 edition of the Divine Comedy’, in H.-T. Shulze Altcappenberg, ed. Sandro Botticelli. The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2000), pp.326-33.

Simon Gilson, Dante and Renaissance Florence (Cambridge : CUP, 2005), chs 5, 6.

Lucia Battaglia Ricci, Dante per immagini. Dalle miniature trecentesche ai giorni nostri (Turin: Einaudi, 2018), pp.106-113.

Also see the Dante in Oxford 2021 project page, part of the TORCH Humanities Cultural Programme.