The Gothic Tower at Wimpole: Knowledge Exchange

‘Mithraic Groves and Gothic Towers: Reuniting the Lost Literary Legacies of Wrest and Wimpole’ is a one-year Knowledge Exchange between the University of Oxford, English Heritage, and the National Trust. The project aims to uncover the vibrant intellectual culture that characterised Wrest Park and Wimpole Hall in the eighteenth-century when both properties were owned by Philip Yorke, second earl of Hardwicke, and Jemima Marchioness Grey.

As Halloween draws near, the word ‘Gothic’ prompts a host of seasonal associations: ivy-clad ruins with pointed arches, crypts, vampires, darkness and horror. But what does ‘Gothic’ really mean? Is it a literary genre, an architectural aesthetic, an archaic font, a dress style, or all and any of these? In this blog we explore the Gothic’s enduring appeal and explain why we might find ruined castles in eighteenth-century gardens.

A brief history of the ‘Gothic’

The historical Goths were Germanic tribes who invaded the Eastern and Western Roman empires in the third century. Early historians condemned the Goths as barbarians who overturned Roman civilisation, and the negative connotations of ‘Gothic’ persisted well into the eighteenth century. To be ‘Gothic’ was to be old-fashioned, crude or ill-mannered.

Yet in the mid-seventeenth century ‘Gothic’ started to acquire a newly positive set of associations. Writers responding to the political crises of the Civil War (1642-51) and Glorious Revolution (1688) looked to the Goths – who broadly included the Saxons – as energetic liberators who rejected Roman governance and lived under a ‘Government of Free-men’ consisting of a sovereign, an assembly of barons and an assembly of commoners.[1]

Defining the Goths largely through their ‘non-Roman’ qualities allowed for considerable semantic slippage. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century political writers were less concerned about historical accuracy than with projecting onto the Goths their own political ideals. Seventeenth-century ‘Commonwealth’ or parliamentarian scholars evoked Gothic liberty to justify resistance to Stuart tyranny; [2] Whig ‘Patriots’ of the 1720s and 1730s used the Gothic legacy to attack the ‘tyranny’ of prime minister Robert Walpole;[3] in the 1770s the ‘Rockingham Whigs’ who had lost their political influence on George III’s accession, drew on the Gothic legacy to counter fears that the king would restore an absolute monarchy.[4]

Gothic Architecture and Eighteenth-Century Landscapes

Just as the Goths politically became the antithesis of the Romans, Gothic architecture, both original and revived, with its irregular asymmetry, pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, was celebrated as an alternative, non-classical aesthetic. The Goths themselves left little more than burial bounds, and so designers had to look elsewhere for their ‘Gothic’ inspiration – at Saxon remains, medieval cathedrals and ruined abbeys.

Frontispiece to Batty Langley’s Gothic Architecture, 1747.

The garden designer, Batty Langley, aptly noted that: ‘every ancient building, which is not in the Grecian mode, is called a Gothic building.’[5] Gothic could be anything non-classical. Horace Walpole, a populariser of the Gothic aesthetic, and author of the first ‘Gothic’ novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764), pitted Gothic against Grecian, claiming ‘it is difficult for the noblest Grecian temple to convey half so many impressions to the mind, as a cathedral does of the best Gothic taste.’[6] Gothic style was acquiring not only political traction but romantic and imaginative potential.

Many people enjoyed Gothic architecture primarily for its aesthetic pleasure. Yet its political symbolism remained potent throughout the eighteenth century. The gardens at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, contain a striking golden ironstone Gothic Temple, dedicated to the ‘Liberty of our Ancestors’. The Temple of Liberty, built by James Gibbs in 1741 at the top of Hawkwell Field, was a key building in Lord Cobham’s political landscaping at Stowe, in which he projected his ideals of Whig liberty as a concrete visual riposte to the perceived corruption of Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, who fell from power in 1742.

The Temple of Liberty, Stowe. Image: Jemima Hubberstey

The Gothic Tower at Wimpole Hall

The Gothic Tower at Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, poses a more complex interpretative challenge. A purpose-built ruin, Wimpole’s Gothic Tower has puzzled scholars over the centuries. The National Trust’s recent prize-winning restoration of the building has prompted new questions about its provenance and meaning. In 1768, Wimpole’s owner Philip Yorke, second earl of Hardwicke (1720-1790) commissioned James Essex to construct the folly as an eyecatcher, reviving a design that the Gothic architect Sanderson Miller had put together for his father in 1749. An entry in The Gentleman’s Magazine (1777) shows that Daniel Wray, Philip Yorke’s close friend, wrote an inscription for the building. Here it is below:

The Gothic Tower on Johnson's Hill on the Wimpole Estate, Cambridgeshire. © National Trust Images/Andrew Butler

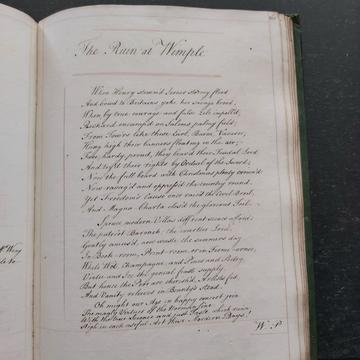

Private collection. ‘The Ruin at Wimple’ in Wrestiana, c. 1773. Image: Jemima Hubberstey

The Ruin at Wimple

When Henry stemm’d Jernes stormy flood

And bowd to Britains yoke her savage brood;

When, by true courage and false zele impell’d,

Richard encamp’d on Salems palmy field;

From Tow’rs like these Earl, Baron, Vavasor,

Hung high their banners floating in the air;

Free, hardy, proud, they brav’d their Feudal Lord

And try’d their rights by Ordeal of the Sword;

Now the full board with Christmas plenty crown’d

Now ravag’d and oppress’d the country round.

Yet Freedom’s Cause once rais’d the Civil Broil,

And Magna Charta clos’d the glorious Toil.

Spruce modern Villas diff’rent scenes afford:

The patriot Baronet; the courtier Lord,

Gently amus’d, now waste the summers day

In Book-room, Print-room or in Ferme-ornee,

While Wit, Champagne, and Pines and Poetry

Virtu and Ice the genial feast supply,

But hence the Poor are cherish’d, Artists fed,

And Vanity relieves in Bounty’s stead.

Oh might our Age in happy concert join

The manly Virtues of the Norman line

With the true Science and just Taste, which raise

High in each useful Art these Modern Days![7]

The poem also appears in manuscript form in ‘Wrestiana’, a private literary manuscript that contains 40 years’ worth of poems and literary fragments that Philip Yorke wrote with select friends from 1742 to 1783.

What are we to make of this poem, designed to appear on the sham ruin at Wimpole? The poem plays on the political idea of Gothic liberty that we have charted above. References to ‘Magna Charta’ and the Baron’s Wars draw on medieval history and celebrate British liberties. Wray deliberately draws on a lexis with an ‘antique cast’ such as ‘Vavasor’, ‘Ordeal’ and ‘Feudal’.[8] Yet midway, the poem shifts from past to present. The ‘manly Virtues of the Norman line’ and the brutal past stand in comic contrast to the present authors’ comparative comfort as they ‘waste’ summer days in their ‘Modern Villas’ with books and champagne. The deliberate echo of Alexander Pope’s Epistle to Burlington (‘Yet hence the Poor are cloth’d, the Hungry Fed.’[9] in the couplet ‘But hence the Poor are cherish’d, Artists fed, / And Vanity relieves in Bounty’s stead)’ places the modern-day present, with its acts of antiquarian architectural homage, in a complicated relationship with the liberty-loving but brutal past.

The complex layering of historical, political, and literary allusions frustrates attempts to interpret the scholarly connotations.

Links to the Wrest Park and the Yorke coterie

One key to interpreting this architectural puzzle might lie in the intellectual games that Yorke and Wray played with garden design some years earlier at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire, the house that Yorke and his literary wife Jemima Marchioness Grey owned before he inherited Wimpole Hall in 1764. Philip and Jemima often entertained their friends at Wrest. At Wrest in the late 1740s they constructed a Mithraic Altar. The altar, hidden in secluded woodland, features two inscriptions in ancient Greek and cuneiform. The building and the inscriptions long puzzled and intrigued both antiquarians and scholars. Visitors also responded directly to the altar and its grove’s mystical, Gothic frisson. The Duchess of Bedford deliberately chose to visit the altar by moonlight, revelling in its otherworldly atmosphere.[10] There are close parallels with Wimpole’s antique Gothic Tower, seemingly steeped in the mists of time, and with a cryptic inscription which requires decoding. Both garden buildings excite and frustrate the visitor’s senses and imagination.

The Gothic Tower is also linked to the Athenian Letters project (1741-3), a mock history of the Peloponnesian Wars that Yorke and Wray wrote with their friends when they were studying at Cambridge. The Athenian Letters, a playful re-imagining of history, combines the authors’ serious scholarly historical interests with a carefully coded satire on contemporary politics. Just as the Athenian Letters blends serious historical interest with playfulness and satire, the Gothic Tower at Wimpole fuses the circle’s antiquarian and political interests with a playful and imaginative historical creativity.

[1] William Temple, ‘Of Heroick Virtue’, Miscellanea. The Second Part. In four Essays, 2 vols (London: printed for R. Simpson, 1705) I, p. 253.

[2] Nick Groom, ‘Eighteenth-Century Gothic before The Castle of Otranto’, The Harp and the Constitution: Myths of Celtic and Gothic Origin, ed. Joanne Parker (Leiden: Brill, 2016), pp. 26-46 (p. 32).

[3] Christine Gerrard, The Patriot Opposition to Walpole: Politics, Poetry, and National Myth, 1725-1742 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 36.

[4] Patrick Eyres (ed), Rockingham Whig Landscapes: New Arcadian Journal 71/72 (2013), pp. 9-11.

[5] Batty Langley, Gothic Architecture, (London: Printed for I. and J. Taylor, 1747), p. 1.

[6] Horace Walpole, ‘State of Architecture to the End of the Reign of Henry VIII’, Anecdotes of Painting in England (London: Chatto and Windus, 1876), p. 112-3.

[7] Private collection, ‘The Ruin at Wimple’, Wrestiana, p. 161.

[8] British Library, Add. MS 35402, fol. 125v [Daniel Wray to Philip Yorke, 30 October 1773]

[9] Alexander Pope, Epistle to Burlington (London: L. Gilliver, 1731), p. 9.

[10] Elizabeth Anson wrote to Jemima Grey that ‘that the Duchess of Bedford, with a Party, have been at Wrest […] They were at the Hill-House by Day-light, they say, but walked over the Garden by Moon-shine; however they saw enough to excite their Curiosity extremely as to the Altar, & taking it for an Antiquity, at least in its Shape & Design they went home & turned over Montfaucon & Kennet, but without success.’ BLARS, L30/9/3/7, fol. 162.

The National Trust Partnership is an award-winning collaboration between Oxford University and the National Trust which creates new opportunities for interdisciplinary research, knowledge exchange, public engagement with research and training at both institutions and beyond.