WillPlay

Where AI meets Shakespeare

As part of this week’s #TORCHGoesDigital! theme of Storytelling, and just in time for Shakespeare's 455th birthday, the TORCH Heritage Programme is taking the opportunity to celebrate this collaborative project of alternative and high-tech storytelling. The project is led by Professor Abigail Williams in collaboration with local games company To Play For, and with support from NESTA’s first ever Alternarratives scheme. We helped this project take off with a Creative Industries Seed Fund.

William Shakespeare, our nation’s most celebrated storyteller, was himself furloughed in 1592 when the London theatres were closed because of the plague. While it is certainly possible that the bard spent much of this unexpected, plague-induced home-time sharing short, comic dance routines with friends, or debating the morality of big cat captivity, no extant evidence attests to it. What we do know is that when one outlet for showcasing his creative talents was shut off, Shakespeare turned to another; in his case, the relatively new, increasingly popular and occasionally controversial medium of print. Now that theatres – along with bars, clubs, cinemas, restaurants, sports grounds and music venues – have once again been closed by a pandemic, we too are seeking out new forms of play.

And we’ve found one. As part of Professor Abigail Williams’s University of Oxford collaboration with local games company To Play For, and with support from NESTA’s first ever Alternarratives scheme, we are using a new machine-learning story-telling platform, Charisma.ai, to create WillPlay. WillPlay is an interactive, AI-powered reimaging of Shakespeare’s plays, and Romeo and Juliet is our prototype. Taking the form of a social-media chat-app, with the accompanying images, emojis and “stories”, WillPlay hopes to allow young people to engage and interact creatively with Shakespeare’s story, language and characters via a familiar, accessible medium. As they message their way through the levels ‘Love’, ‘Hate’ and ‘Death’, players chart their own, unique route through the story, shaping it as they play. Play is still the thing – it’s just a lot closer to the kind of play teenagers want.

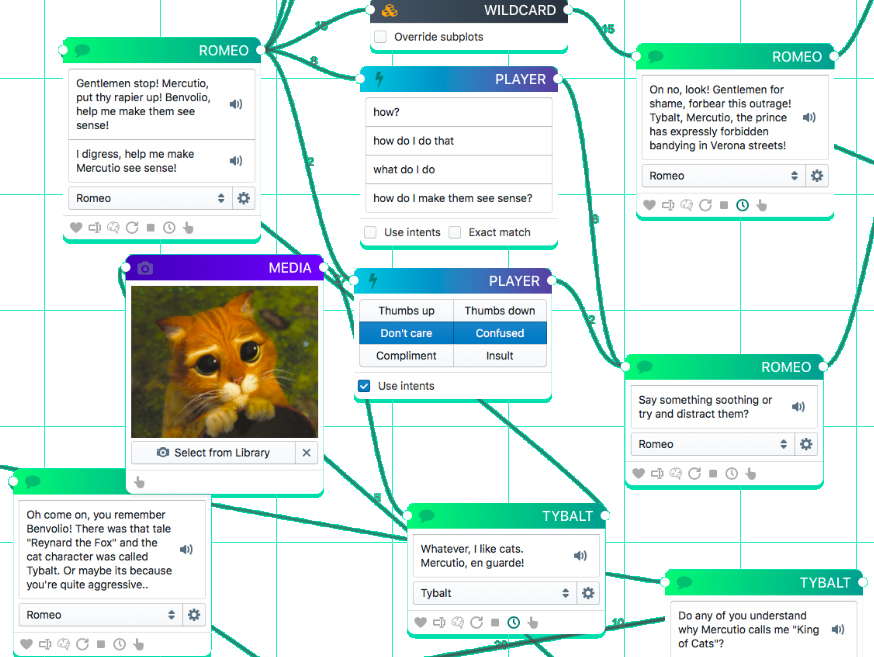

‘Hate’ coding: a section of the writing for the central level of the Romeo and Juliet prototype.

WillPlay is more than just a language tool, a text-book, or an easy way to learn quotations, though it is also all those things. While a hover function allows players to look up vocabulary and access additional information, the combination of Shakespearean language and contemporary colloquialism spoken by the characters enables players to decipher archaic expressions intuitively. But more importantly, by adopting different roles (yourself in the first instalment, a minor character in the second, and a major character in the third), the player in our Romeo and Juliet prototype is encouraged to empathise with the characters and compelled to engage creatively in the process of meaning-making. The countless alternative routes through each scene, meanwhile, allow the player real agency in plot and structure. While key points of action remain fixed (Romeo and Juliet do still fall in love and – spoiler alert – they still die!) how and why you get there becomes the prerogative of the player. Despite the AI technology, the social media wrapper, and a smattering of textual abbreviations, the contemporary, controversial, and collaborative Romeo and Juliet experience that WillPlay will offer is, we believe, truly Shakespearean.

Shakespearean theatre today is revered, civilized, and appreciated in polite silence; but early modern playhouses were raucous, noisy places, where the story that actors were telling had to compete for attention with hawkers and balladeers and even flamboyant audience members sitting on the stage. The repertory system meant a different play was performed almost every day, with new plays carrying particular currency. This rapid turnover gave performances a more improvised quality than we are used to now, and it meant audiences often didn’t know what to expect from the plays they went to see. If early modern audiences didn’t like what they were seeing, moreover, they intervened. One anecdote describes a company of actors being pelted with oranges until they changed out of their tragic costumes mid-play and performed a comic piece about “merry milk-maids” instead. Elsewhere, there are tales of dissatisfied playgoers flooding the stage; of spectators loudly confessing their crimes upon witnessing a murder in a play; of audience members accidentally injured by stage weaponry. Playgoing was far from the passive experience we might expect. Audience members were active, involved, sometimes unruly participants in the drama.

Today theatres such as Shakespeare’s Globe aim to recreate something of this early modern playgoing experience with their original practice productions, emulating the costumes, music, staging and even architecture of 16th century theatre. Through WillPlay, we hope to pursue a different kind of original practice, using new and radically different technologies to create an experience more closely analogous to that enjoyed by the sixteenth-century playgoer. WillPlay turns audience into player, spectator and critic. Reimagining Shakespeare’s dialogue as online group chats, it invites users to take part in the conversation, enabling an updated version of the interactive, immersive engagement experienced in the early modern playhouse. This is Shakespeare that looks and feels as familiar in 2020 as ruffs and hose did in 1599; and the familiarity of the format makes it easier to draw out contemporary thematic resonances already present in the play. Shakespearean stories are neither irrelevant nor inaccessible for young people in 2020, far from it. In its characters, plotting, and poetry, Romeo and Juliet remains as engaging and as relevant today as it’s ever been. This is simply a matter of shifting the play from one storytelling platform which artificially imitates real life to another.

In the process, we ourselves are having to become storytellers: we realised early on that excerpting snippets of Shakespearean dialogue and pasting them into successive message nodes on the Charisma.ai platform simply wasn’t going to cut it! We’re learning, slowly, how to anticipate and reply to player responses at each stage of the story, and we’re also learning how to shape them, so that players can engage meaningfully and creatively with Shakespeare’s narrative – can play around within it – without feeling compelled to veer too far from the essential plot. There’s still lots of work to be done on WillPlay, but we’re lucky to learning from the best: a writer whose stories have been engaging audiences and inviting multiple (and sometimes even contradictory) interpretations for over four centuries. WillPlay is by no means a comprehensive Shakespeare experience. Eventually, we envision it working in tandem with theatre trips, classroom learning and, of course, full readings of the plays. In a time, however, when many of those options may not be available, we hope WillPlay can get young people excited about Shakespeare and new forms of storytelling, all from the comfort of their own phones.

Felicity Brown is a 2nd year English DPhil student at Jesus College, working on the adaptation and reception of the Arthurian legend in early modern drama. Rachael Hodge is a 3rd year English DPhil student at St John’s College, working on generic fluidity and playfulness in the early years of the professional 16th century theatres.