Napoleon in Lockdown

A Summer Internship with The British Napoleonic Bicentenary Trust

The TORCH Heritage Partnerships Team, working closely with the University of Oxford Careers Service, set up and funded this 4-week summer internship with The British Napoleonic Bicentenary Trust.

“It is most difficult to obtain absolute certainties for the purposes of history. Fortunately it is, in general, more a matter of mere curiosity than of real importance. [...] What then is, generally speaking, the truth of history? A fable agreed upon.”[1]

I must admit, I somewhat share Napoleon’s scepticism on the truth of history. Despite being something that I have dedicated my life to, and which brought me to Oxford, I sometimes find myself wondering what it is all truly for. What great importance is there to history other than to satiate the ‘mere curiosity’ of a few fanatics and fetishists? What use is knowledge without any social function? Having studied history throughout my higher education for the better part of seven years, I am often reminded by my more pragmatic peers that there are simply no realistic careers in history. It is all good and well for the passionate amateur and the part-time retiree, but unless you are willing to condemn your life to the toil of academia, then you might as well abandon the archives and find a real job. Simply put, there is no future in the past.

This was very much on my mind when I arrived at Oxford last year. After effectively being comfortably institutionalised for five years, I suddenly became aware that I would soon be expected to apply the skills I had acquired to something actually useful. It was, then, a most fortunate blessing when I encountered an email from The Oxford Centre for Research in the Humanities (TORCH) sitting in my inbox. It was a newsletter which was inviting students to attend the Heritage Pathway events. I discussed it briefly with a fellow member of my cohort, who was far more knowledgeable about the heritage sector than I, and vividly remember having a little epiphany along the lines of, “Yeah, I quite like the idea of doing museums”. I attended the first Heritage Pathways event and became a loyal attendee for the remainder of the academic year, eventually following the seminars on Zoom. I came for the free sandwiches, but I stayed for the incredible insights and opportunities that Heritage Pathway speakers had to offer. After that first event, I suddenly realised that there was a purpose to my study and, perhaps more importantly, there was some small glimmer of hope that one day someone might pay me to look at old things.

Through Heritage Pathway I grew familiar with members of the Heritage Partnerships Team at TORCH and the Oxford University Heritage Network, and became aware of further opportunities available - especially the Micro-Intern Programme. I have undertaken two separate Micro-Internships since then, and both have only widened my horizons to the professional possibilities within the arts and heritage sector. As I became more familiar with the networks, the organisations and the funding bodies that exist, I grew more confident in applying for things, sending unsolicited emails to very busy heritage workers, and daring to imagine a life with one foot outside the walls of a university. It was refreshing, and gave me a totally different outlook on my own academic work. Suddenly, I was seeking further possibilities within my own research and constantly asking the question that so many historians seem reluctant to entertain, “Who cares?”. As it turns out, people care, quite a lot of people care, just as long as you frame your research in a way that is actually digestible.

In the last month of my degree, I received a fortuitous email from my supervisor. He had been contacted by a colleague in York who had recently become a trustee of ‘The British Napoleonic Bicentenary Trust’; a charity who were preparing to commemorate 200 years since the death of Napoleon. The trust was looking for someone who could manage their digital media - an aspect they had overlooked until current circumstances made that impossible - and wondered if my supervisor knew an appropriate appointee. There were really only two criteria for the job: you needed to be social media literate and you needed to care a lot about Napoleonic history.

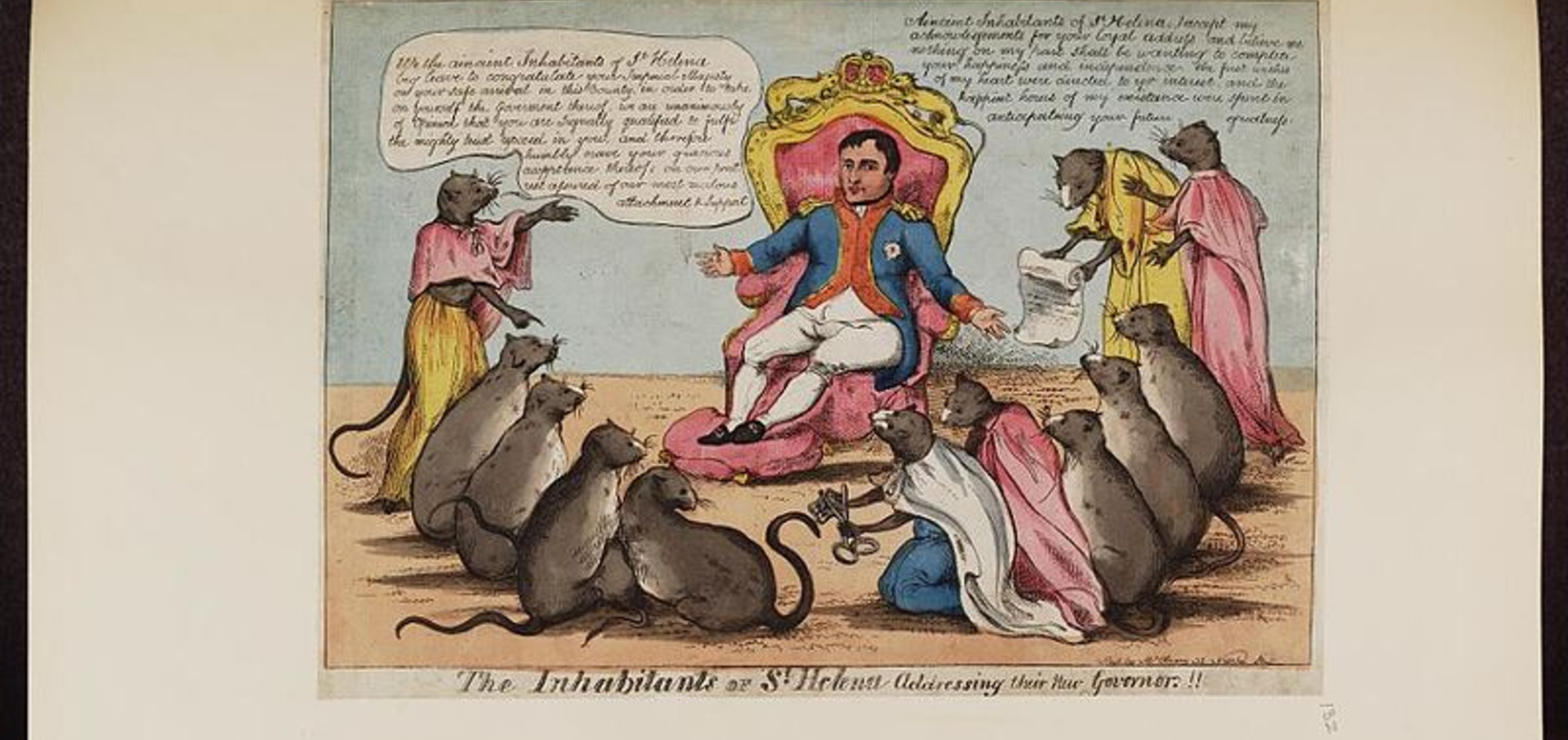

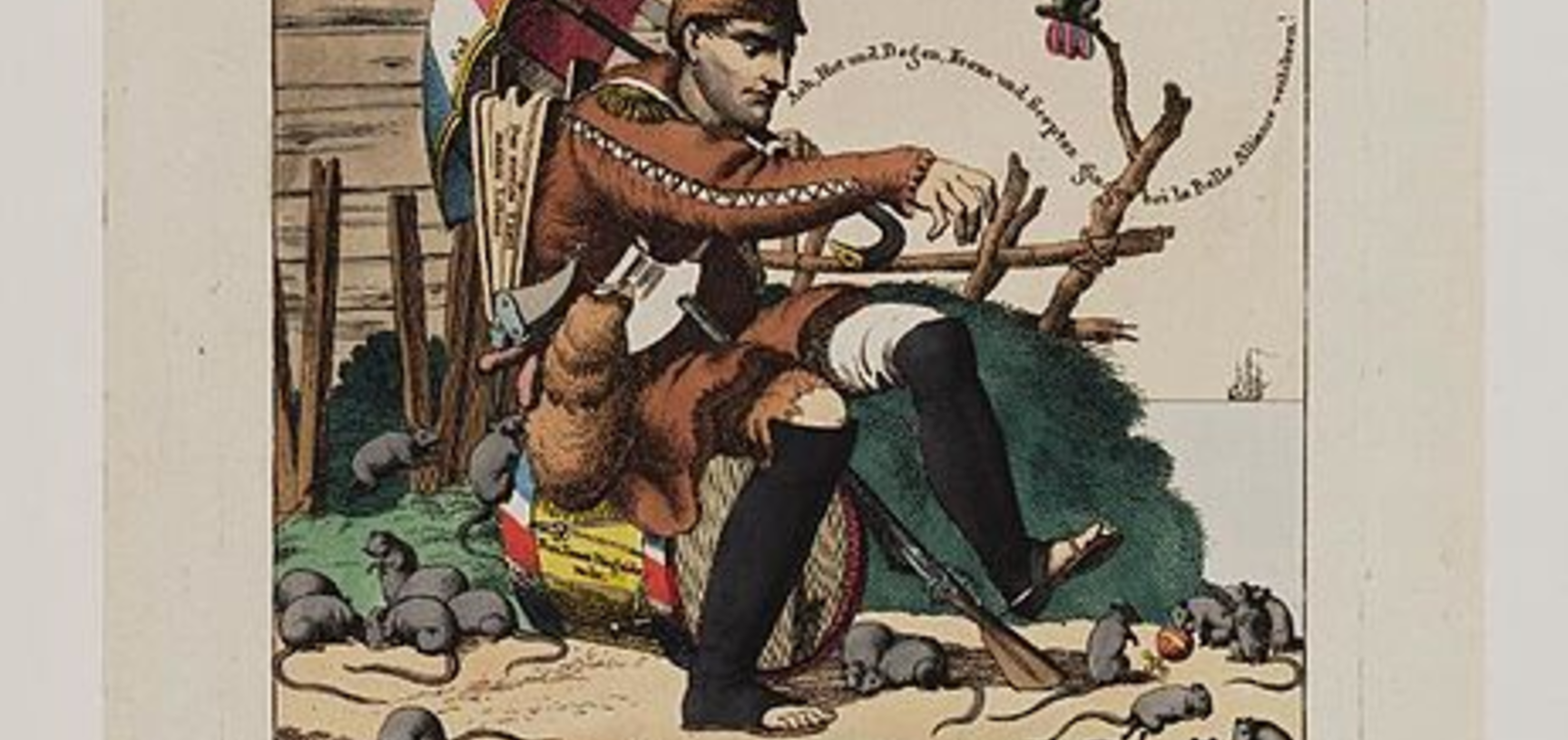

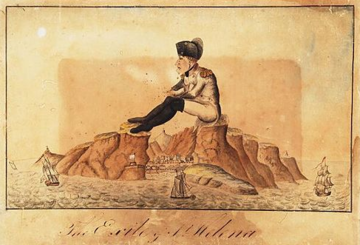

My experiences over the course of this academic year have not only given me professional skills, but had totally changed how I approach history and heritage. This project wasn’t just about Napoleon. It was about the island of St. Helena, where he spent his final years in exile. It was about the geography, the culture, the politics, the memory, the legacy and the biography of all the other characters on the periphery of this story. Furthermore, this was about the native Saints, and about the enslaved people who lived and laboured on St. Helena during Napoleon’s time in exile. This was about Napoleon’s own relationship with colonialism and slavery and about how the world was shaken by the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Before I allowed child-like glee to flood my brain with romantic images of Bonaparte on horseback, I took a step back and saw a larger picture. Napoleon has had his fair share of the limelight in the last 200 years. Perhaps this could be an opportunity to turn that light on some lesser known stories?

My involvement in the project is two-fold: to maintain digital media and to organise collaborative events for the trust. The creative freedom I have been given in the project has been particularly exciting. I’ll continue working on this up until May 5th 2021, when we can mark 200 years since Napoleon died. I don’t want to bore you with sentimental poetry, but I’m going to anyway: sitting completely alone in my flat for four months straight has made the subject of exile and isolation particularly pertinent. I worried what a Summer in isolation might look like. With my degree complete and most places closed, I foresaw a long and empty space before me, absent of purpose or productivity. However now, although he is 200 years and 9000 miles away, Napoleon and I keep each other company on a fairly regular basis. We have become trans-historical pen pals. Through a mesh of Zoom calls, Google docs and email threads that supplement the inability for social interaction, I am able to pursue a truly important and exciting heritage project.

[1] Emmanuel-August-Dieudonné de Las Cases, Mémorial de Sainte Hélène: Journal of the Private Life and Conversations of the Emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena, Vol. 4, Part 7 (London, 1823), pp. 251-252.

Alexander Kither is a graduate student in Modern European History at St. Anne’s College. His research interests are concerned with the politics of culture in the nineteenth century, with a particular emphasis on the status of art and antiquities during the Revolutionary-Napoleonic period. He is interested in the development of digital humanities and will be undertaking a graduate position in this field at the Institute of Historical Research following the completion of his degree later this year.

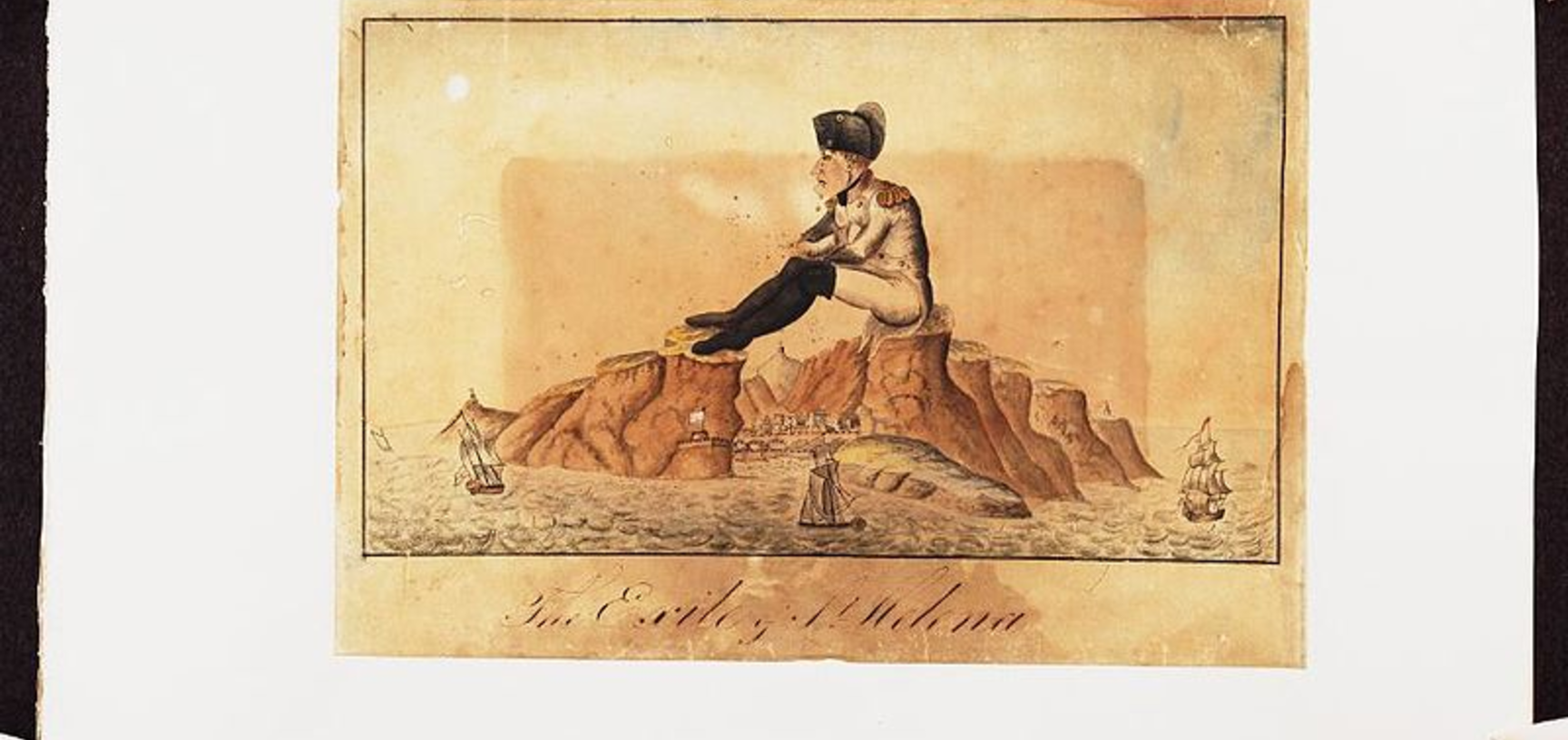

The exile of St. Helena. Bodleian Library Curzon b.6(27)