The Land Remembers

Mapping and Understanding Cultural Landscapes in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta

The Heritage Partnerships Team is pleased to feature this new series of blog posts, exploring the cultural landscapes of Southwest Alaska. starting with the Yukon-Kuskokwim (Y-K) Delta. We have supported this research project with Heritage Seed Funding. Follow this space to find out more about the Agalig river and more!

Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is one of the largest river deltas in the world, consisting of vast tracts of subarctic tundras, lakes, and long winding rivers.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim (Y-K) Delta, of Southwest Alaska, is unlike any other place in the world. This vast region of is home of the Yup’ik (pl. Yupiit) people, who hunt, fish, and gather in a way that is similar to that of their ancestors. For much of the year this subarctic wetland tundra is covered by ice and snow with a brief period of of lush greenery during the summer months.

Quinhagak is situated on the Bering Sea coast, with access to two major salmon rivers, the Qanirtuuq (Kanektok) and Agalig (Arolik). However, like other villages on this coastline, its infrastructure, lands, and heritage is at risk from climate change.

Quinhagak is a community of around 700 Yupiit by the shore of the Bering Sea. Since 2009, the community has supported and co-funded the University of Aberdeen’s Quinhagak Archaeological Project to excavate the nearby ancestral village of Nunalleq before it is destroyed by rapid climate change-driven coastal erosion.

Meta Williams helping us identify vegetation growing around the Nunalleq archaeological site.

With the excavation phase of the project winding down for now, and with the foundation of the Nunalleq Museum at Quinhagak to house the 80,000 artefacts recovered from the site, attention now turns to the other important cultural places in the region. After two years of planning, our small three-person team have returned to Quinhagak to map this beautiful and endlessly fascinating cultural landscape. Working alongside Qanirtuuq Inc, the Alaska Native corporation representing Quinhagak, we are using drone-based remote sensing and ethnographic interviews to fully understand how past and present Yupiit lived their lives here (Please see our article, published days ago with our main local collaborators, for details on our planned research agenda for the summer). Our work here is funded by a Heritage Seed Fund grant from TORCH, along with an Emslie Horniman Scholarship grant from the Royal Anthropological Institute, and the Hampden-Sydney summer research series.

We have been in Quinhagak for over two weeks, and things are progressing nicely. Working with community member Meta Williams (Alaska Christian College), we are trialling a new technique to match vegetation patterns captured by the drone with Yup’ik understandings of flora.

Cultural places in the Y-K Delta, like remote subsistence camps and archaeological sites, often display vegetation patterns that are caused by human activity— for example, the disposal of waste by past peoples can enrich the soil with phosphates in this nutrient-poor environment, causing a specific communities of species to grow in the area for centuries after the fact. Cataloguing the vegetation patterns of different types of cultural sites is the basis of Jonathan Lim’s DPhil project at Oxford.

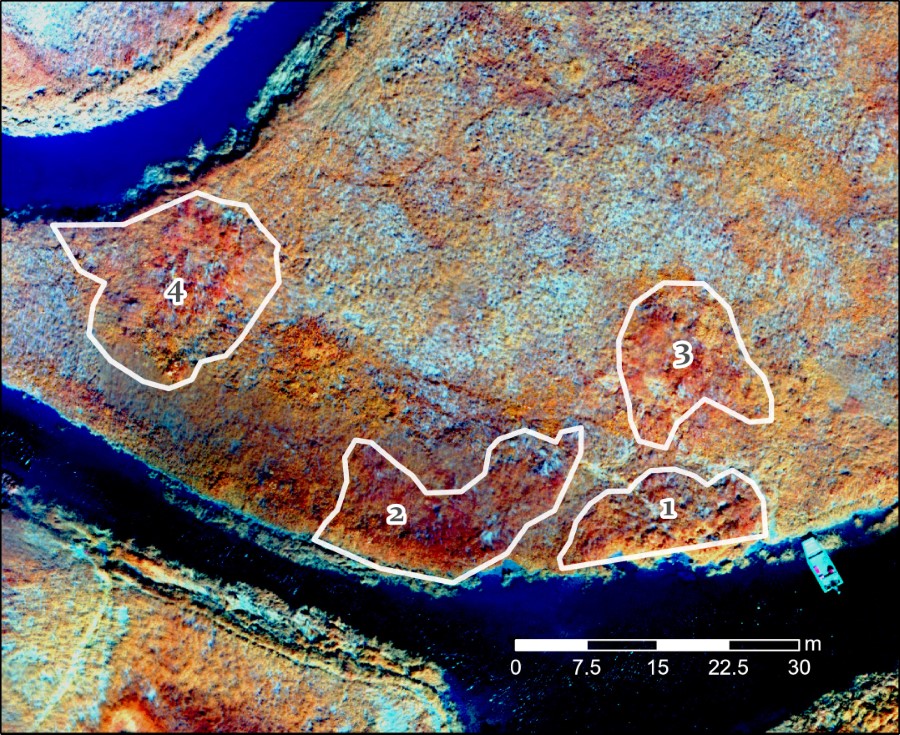

Artificially colourised aerial view of an abandoned village site north of Quinhagak. The white outlines represent collapsed sod-built structures dated to 200 years ago, and the vegetation growing on top of these is noticeably different. We used a multispectral camera, which captures spectra of light beyond what is visible to the human eye— this allows us to better highlight vegetation changes that may be caused by past human activity.

John Smith recalling the Y-K Delta of his childhood, growing up in Hooper Bay.

We have also conducted interviews with community Elders. One such individual is John Smith who spoke to us about how the Yup’ik way of life has changed from his youth. Although he did not grow up in Quinhagak, John’s poignant words offers a glimpse into a dynamic landscape now lost to time— a world without snowmobiles, motorised boats, and ATV’s, where people lived in remote camps in the wilderness throughout the year rather than being based solely in a central village.

The spectre of climate change-induced erosion looms large over Quinhagak. Another aspect of our project involves identifying Alaska Native allotments that are about to be lost to the rapid shifting of waterways and coastlines, a problem exacerbated by melting permafrost. We interviewed former Quinhagak mayor Willard Church, who expressed his fears of imminent loss of infrastructure, livelihoods, and ancestral lands if swift action is not taken soon.

Waterway change has always been a reality of life in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, but erosion has accelerated dramatically in the last hundred years, coinciding with a warming global climate. Infrastructure damage like this at Quinhagak’s old airport road, causes by a sudden waterway shift upriver, poses a danger to residents and their property.

Quyana (thank you) for joining us today. We will post another update on our progress in two weeks, with a focus on the Agalig river

Jonathan Lim is a DPhil student at the School of Archaeology, University of Oxford. His research involves the use of spatial technology and ethnoarchaeology to understand cultural landscapes in Southwest Alaska.

Dr. Sean Gleason is Assistant Professor of Rhetoric at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia. His research interests are in oral history and subsistence knowledge. He is the external supervisor of Jonathan Lim.

Daniel Marsden is an undergraduate at Hampden-Sydney College majoring in history with a minor in rhetoric. His research interests are in colonial interactions and associated historical policies. He is currently learning to operate differential GPS units and process data in ArcGIS Pro.

Acknowledgments

With deepest thanks to the community of Quinhagak, especially Warren Jones, Willard Church, Mike Smith, Fannie Berezkin, Jessica Alexie, John Foster, Meta Williams, John Smith and others. Thanks also to the University of Aberdeen’s Quinhagak Archaeological Project, especially Dr. Rick Knecht. Jonathan Lim is supervised by Prof. Rick Schulting and Dr. John Pouncett (School of Archaeology, University of Oxford).

Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is one of the largest river deltas in the world, consisting of vast tracts of subarctic tundras, lakes, and long winding rivers.